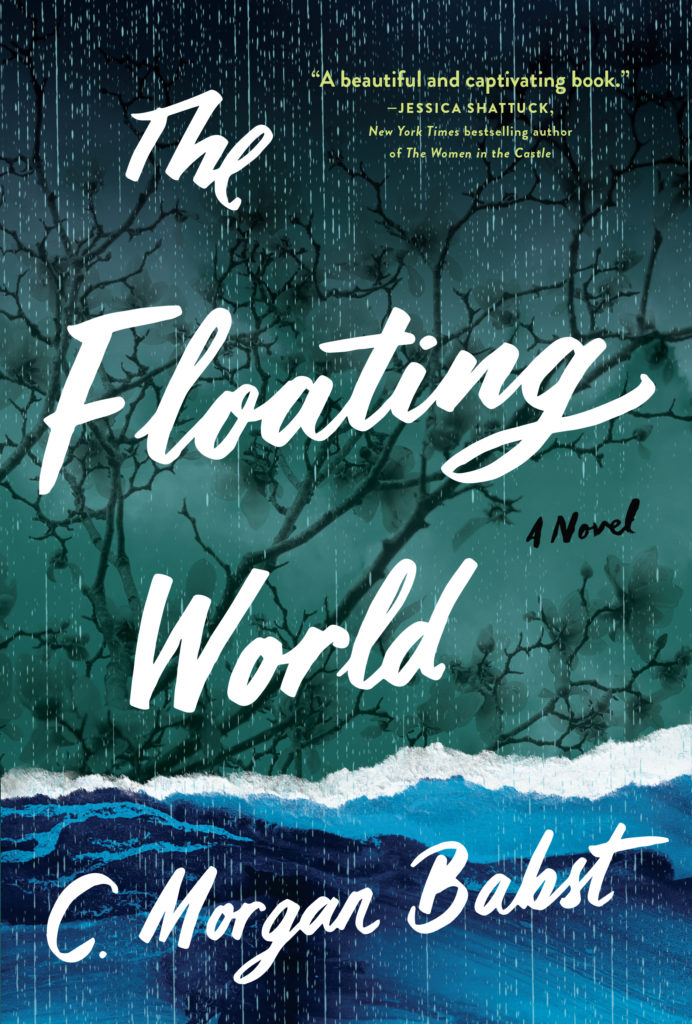

Welcome to our #FridayReads feature on the blog, where we’ll be excerpting a chapter of one of our favorite books to start your weekend. This week, it’s C. Morgan Babst’s dazzling debut The Floating World, which takes readers into the heart of Hurricane Katrina with the story of the Boisdorés, whose roots stretch back nearly to the foundation of New Orleans.

Scroll down for an excerpt.

The Floating World

Forty-Seven Days after Landfall

October 15

The house bobbed in a dark lake. The flood was gone, but Cora still felt it wrapped around her waist, its head nestled on her hip. She laid her hands out, palms on its surface, and the drifting hem of her nightshirt fingered her thighs. Under her feet, lake bed slipped: pebbles and grit, mud broken into scales that curled up at their edges. Her legs dragged as she moved under the tilting crosses of the electrical poles, keeping her head tipped up, her mouth open. Her fingers trailed behind her, shirring the water that was air.

The broken concrete of the driveway seesawed, and the kitchen window was still open as she and Troy had left it when they came for the children, the shutters banged flat against the weatherboard. The little boy had jumped at her from the windowsill, naked except for a pair of water wings, a frenzy of brown and orange. She closed her eyes—Blot it out—but even in the dark, she could feel his head cupped in her hand. She could hear Reyna screaming. She saw herself rocking in the pirogue in the thick air, the little boy nestled against her chest. The flood had floated them high.

Now, she got up and put one foot against the siding, two hands on the sill. She strained, scrambled, jumped. She hauled her body up and perched in the window, her muscles trembling.

The moon cast Cora’s shadow, long and black, across the kitchen floor, where a woman lay, her face no longer a face, only a mess of blackened blood. She shut her eyes. Blot it out. But when she looked again Reyna’s body still lay curled, as if in sleep, around the shotgun that was missing from the house on Esplanade, her arm trailing awkwardly behind her like something ripped apart by a strong wind.

Blot it out, Mrs. Randsell had told her. So she had been sleeping. Drugs like a dark river to drown in. But now she felt again the gun recoil against her shoulder. Saw again the light of the blast in the high hall. Blot it out, but she could see as clear as if it were happening again in front of her now: Troy standing above her at the top of the stairs, the little boy reaching out to stroke his mother’s smooth, unmaddened brow. She saw Reyna press her face against the window, her eyes plucked out by birds. Cora looked down from the window, and the pool of blood whirled through the woman’s face, through kitchen floor, pulling her under. The storm threw a barge against the floodwall. The surge dug out handfuls of sand. The Gulf bent its head and rammed into the breach until it had tunneled through to air. The lowest pressure ever recorded, the radio voices said, and the vacuum pulled at her, her nightdress snapping against her body like a flag.

Night poured in through the window. Stars streaked down through the sky. She would fall. She was falling. The flood’s reek rose.

***

Thursday

October 20

Today, Tess told herself, they would make it to the hedge.

The confederate jasmine that Laura Dobie had trained along her iron fence had begun to insinuate itself into the boxwoods, and ripping it out was the least they could do. The least we can do, Tess told Cora, considering the Dobies are lending us their house. The main objective, of course, was just to get Cora out of bed, but Dan Dobie really had been so sweet—the way he’d just thrown his house keys at her through the car window as he and Laura headed out of town.

“Keeping their house from falling down in their absence is really the very least we can do,” Tess said, petting her daughter’s arm, and Cora slid her skeletal legs off the mattress of her childhood bed, let her feet fall on the padded floor of Dan’s home gym. Cora then stood up under her own power and walked, her bony knees trembling, all the way to the hall door.

Cora’s nightgown was half-tucked into the seat of her underpants, but Tess had not made a move to fix it, worried that that would break the spell. Her daughter was on her arm now. They were descending the stairs. Tess held onto the banister, feeling a bit unsteady herself.

She saw how one might think neurosis could be catching. They used joke about it in the office—I think you’ve caught Verlander’s kleptomania, Alice—but emotional contagion was a real thing, at least according to Hatfield. Since moving alone with Cora into the Dobies’ house, Tess had had to fight not only against the ubiquitous grief but against the urge to sink into the mattress and disappear, as Cora was trying so desperately to do. Tess had to remind herself that Cora had experienced a direct trauma—had seen the storm with her own eyes, had been out in the flood in a pirogue, and to top it off had had the tremendous bad luck to rescue Mrs. Randsell, only to watch her die of a stroke just one week after they’d finally made it to Houston. Still, when Tess tried to be happy that Del was coming today—that in a few hours her healthy daughter would be here with her feet up on the Dobies’ coffee table, helping her drink a bottle of chardonnay—she only felt exhausted.

For now, though, she and Cora were going down the stairs. They took one at a time, Cora staring hard at her toes. Her feet were dirty again, God knew why. Again, her dinner tray had not been touched. Again, she smelled oddly of river mud. But they reached the bottom of the stairs without incident—Tess told herself that this was progress.

When she tugged her daughter’s nightgown free so that it fell over her legs in a muslin cloud, however, Cora stopped short in the middle of the foyer and, as Tess had feared, refused to budge. But yesterday, they’d gotten as far as the front porch; today they would make it to the hedge.

“Cora, come on now,” Tess said, her hand calm in her daughter’s hand. “Your sister’s coming today. We need to make things pretty for her.”

Cora didn’t move.

“We can’t let Del see how we’ve been letting ourselves go, can we?” she asked, offering Cora a chance to agree. “Won’t it be nice to just work a little while in the fresh air?”

“Fresh,” Cora said, her face full of stubborn sleep, like the face of an awakened child. She shook her head slowly. “No.”

Tess could admit that she would have liked to stay in bed. The world outside was hot and sour, and it was nice to take refuge in the air-conditioning, among the old mahogany furniture she and Joe had rescued from their house on Esplanade. The curtained rooms were quiet, and Laura’s ugly high pile carpets were so soft beneath your feet. But you couldn’t just sleep. Already, Tess had cleaned the Dobies’ kitchen cabinets with Murphy’s Oil, washed the mustiness out of all of the sheets, polished the Marleybone silver that had traveled with her to Houston and back again. You couldn’t sleep. She had been telling Cora this since Houston, even as she handed over the Ambien. You couldn’t just sleep until it was over, even if you were drained beyond your last drop, reamed out like a lemon down to the pith. You couldn’t just sleep, even if that was the only thing that felt good. Even if, alone on the Dobies’ nice pillow-topped mattress, Joe not in it, Tess slept like a baby. Every morning now, she woke up clutching her pillow, sprawled out and drooling. But she got herself out of bed.

“Come on now—” she reached out her two hands, remained upright, cheerful. Project the affect you would like to see echoed in the patient. “It’s like cold storage in here.”

Tess turned and opened the front door, let a rectangle of yellow sun swoon across the barge boards, but Cora backed away.

“Cora,” Tess said, in the same calm, conspiring voice.

Cora’s eyes, ringed in dark circles like the city’s flooded houses, were blank.

“Cora,” she said again, more forcefully now.

But Cora just stared straight ahead as though she knew no one by that name.

Hooked? You can buy the book here.

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

No Comments