Welcome to Workman’s #30DaysofGiving! This holiday season, we will be excerpting from some of our favorite books of the year and giving readers the chance to win a copy. Follow along by visiting our master digital advent calendar, and use the hashtag #30DaysofGiving on social media for daily updates.

WILDLIFE SPECTACLES by Vladimir Dinets (Day 22)

The following passage is excerpted from the book.

5 Amazing Winter Wildlife Spectacles

1. The introduced European starling is another nomad that forms huge flocks in winter. These flocks are famous for the amazing aerial maneuvers performed by thousands of birds apparently in absolute synchrony. Scientists have gone through many years of research and a lot of computer modeling to figure out how the birds do this, but they still don’t fully understand the dynamics. There is no leader in a flock; each bird is capable of simultaneously gradually learned to live side by side with people, and in the second half of the twentieth century started forming huge urban roosts, often on university campuses. These roosts allowed them to escape shooting by farmers and predation by great horned owls, but there was a price to pay: such huge concentrations of birds were susceptible to disease and parasite infestations.

Raptors, songbirds, and other migrants, often including bats and monarch butterflies, gather in huge numbers in the fall at Cape May, NJ, and in Fisherman Island National Wildlife Refuge, VA. Up to 4000 golden eagles fly over Mount Lorette, AB, every September. One of the largest vulture roosts can be seen in winter in Versailles State Park, IN. A large communal roost of white-tailed kites can be seen from December to February at the intersection of Moddison Avenue and Carlson Drive in Sacramento, CA.

Starling flocks can form cloudlike masses. Photo © Anastasiia Tsvietkova

2. For seals and sea lions, the sequence and proximity of mating and birth is noteworthy. Childbirth (or, in this case, pupping) is immediately followed by mating. Male fur seals, elephant seals, gray seals, and sea lions stake out territories at breeding rookeries a few weeks in advance, eagerly waiting for females to arrive and give birth. Then, in a practice few human females would likely endorse, the males mate with the new mothers within a few days of the birth—sometimes within hours. Pregnancy lasts exactly one year. It sounds simple enough, but in reality this is a grueling affair for both sides. Males endure weeks of bloody fighting—so exhausting that some of them can’t recover and die soon after. Only very few bulls actually get to breed: among elephant seals, just a few males out of a hundred sire ninety percent of the offspring. Such extreme selection has made them highly adapted for battle.

The best place to see fighting and mating elephant seals is the viewpoint on Hwy 1 north of San Simeon, CA, where fighting reaches its peak in December and pups are born in January. Año Nuevo State Park, CA, is also popular. The largest rookeries of northern fur seals are on Pribilof Island, AK. California sea lions mostly breed on the Channel Islands, but there is now a rookery near Fisherman’s Wharf in Monterey, CA. Steller’s sea lions mostly breed in Alaska. At Point Bennett in Channel Islands National Park, CA, you can see breeding California and Steller’s sea lions, northern and sometimes Guadalupe fur seals.

Male northern fur seal with his harem. Photo © Vladimir Dinets

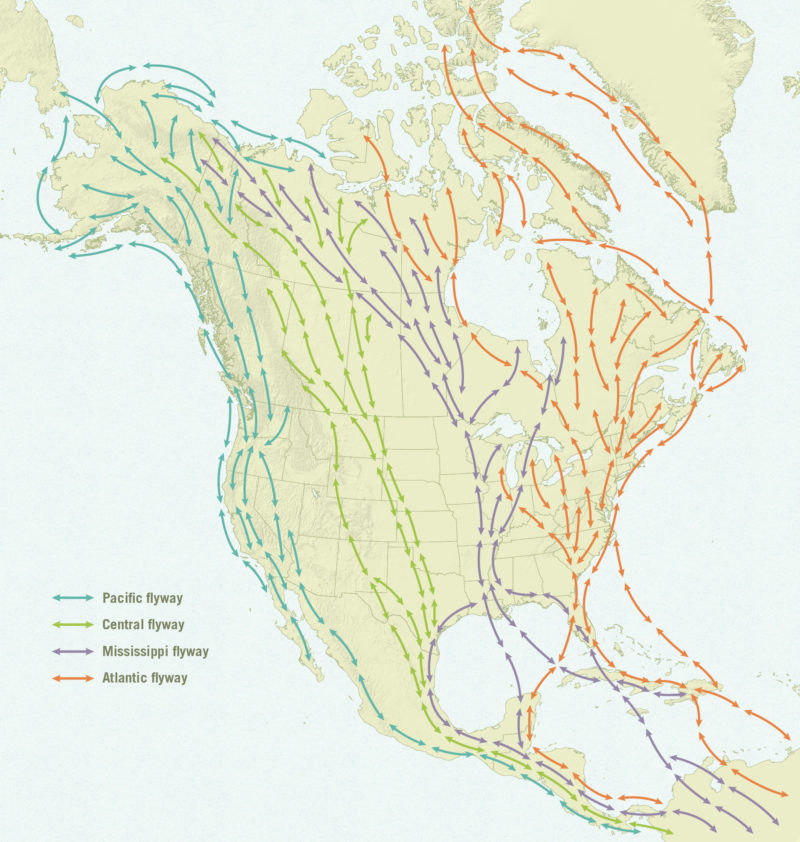

3. Almost all North American birds migrate every year. For some, the migration is less than a mile long, but most have to embark on a long, exhausting, increasingly dangerous exodus spanning hundreds and even thousands of miles. Every species and even subspecies has its own unique routes of migration, but the geography of the continent is such that many get channeled into the same routes for parts of their journeys. These routes, where huge numbers of birds can be seen at the same time, are called flyways. Traditionally, four major flyways are recognized; each of them could be subdivided into smaller ones—but it’s easier to not get too technical.

An Arctic tern. Photo © Vladimir Dinets

The Pacific Flyway begins in the Arctic and ends in the Antarctic. It is so long that only one bird, the Arctic tern, actually flies its entire length—28,000 miles round-trip. Unlike waders, terns can rest on flotsam (if the weather permits) or ship rigging; their reward for traveling six months out of each year is that they can enjoy twenty-four hours of daylight for the other six months (May–July in the Arctic and then November–January in the Antarctic). Other birds use only parts of the Pacific Flyway; in some cases just a hundred miles (like some Allen’s hummingbirds that nest near Santa Barbara and winter around San Diego).

North American Flyways. Photo © FreeVectorMaps

4. Monarchs follow a network of flyways remarkably similar to those used by birds. Some fly along the Atlantic coast to Florida, where they remain fully active all winter, or to Cuba. A few overwinter along the Gulf Coast or cross the Gulf of Mexico. But the majority of monarchs living east of the Rockies cross Texas (either along the coast or through the Hill Country) and fly all the way to the mountains of Central Mexico. The wintering sites of these millions of butterflies weren’t discovered until 1975. All monarchs gather in a few old-growth patches of fir trees, and hang from branches in immense congregations. On warm, sunny days they fly around, feed and breed, but sometimes they have to hang in those trees for weeks, waiting out snowstorms and freezes.

Wintering monarch butterflies can be best seen from November through January at the following locations in California: Natural Bridges State Beach near Santa Cruz, Monarch Grove Sanctuary in Pacific Grove, Pismo Beach in Oceano, and (the largest concentration, up to 100,000) at Goleta Butterfly Grove in Goleta. Migrating monarchs tend to be particularly numerous in Texas Hill Country in mid-October and along the Texas coast in late October; the coast of Louisiana is also followed by large numbers in some years (see monrchwatch.org for updates).Long-tailed skippers migrate in large numbers along both coasts of the Florida Peninsula from late September until November and again in April. American snouts migrate across the lower Rio Grande, TX, in late September, sometimes in millions or even billions.

Wintering monarchs in California. (Photo © Vladimir Dinets

5. People usually think of spring as the time of love, but in reality every season in North America is breeding season. Wolves, ravens, and great horned owls begin courtship in February; a few bat species mate in wintering caves; deer, caribou and mountain goat rut can stretch until January. It’s always a treat to watch fighting deer, bison, muskoxen and bighorn—but moose and elk ruts are particularly dramatic. As a result of males constantly trying to impress females, and females trying to pick the best mate, an arms race of sorts often unfolds: males try to cheat, and females try to see through the cheating. The textbook example is the male elk: as it matures, it develops a loop in its trachea that makes its voice deeper, as if it were larger. Interestingly, the only other species known to use the same trick is humans: men’s larynxes descend during puberty, making their voices sound more masculine. Studies have found that most women find deep male voices sexier.

Elk rut usually peaks in late fall; the best places to see it are Banff and Elk Island National Parks, AB, Charles M. Russell National Wildlife Refuge, MT, Valles Caldera National Park, NM, Grand Teton National Park, WY, Rocky Mountains National Park, CO, Redwood National Park, CA, Hatfield Knob in North Cumberland Wildlife Management Area, TN, and Elk Country Visitor Center near Benezette, PA. Deer rut in November in the North but as late as February in Florida.

Bull elk locked in battle. (Photo © Vladimir Dinets

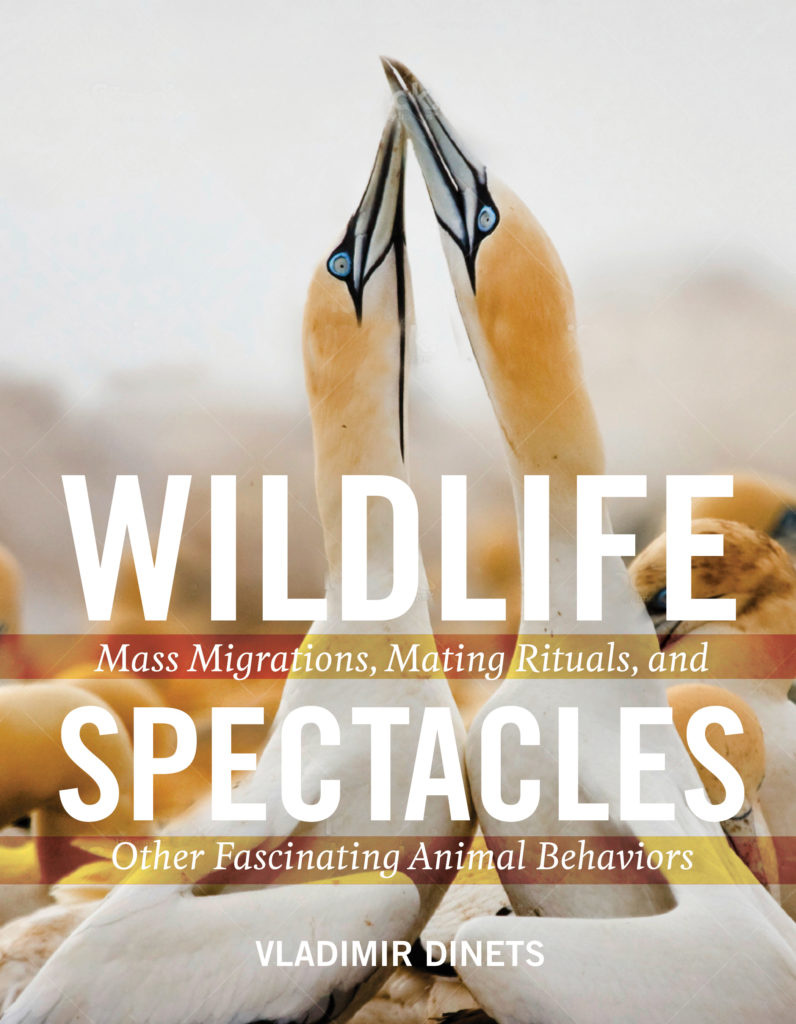

About the Book:

Equal parts nature guide, adventure story, and coffee table book!

People are captivated by wild animals—by their strength and their size and by the things they do to stay alive. In Wildlife Spectacles zoologist Vladimer Dinets dives deep into this wonder, allowing curious readers to discover just how spectacular wild animals can be. In the rich, fully illustrated pages you’ll discover the migration of gray whales along the Pacific coast, the dancing alligators of the Everglades, the synchronized blinking of fireflies near Tennessee, the swarms of feeding bats over the Mississippi River, the blue-glowing scorpions of the Southwest desert, hundreds of wintering tundra swans in New Jersey, and much more.

Buy the Book

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

Still need help finding a gift? Message our Holiday Hotline for personalized suggestions.

No Comments