Welcome to Workman’s #30DaysofGiving! This holiday season, we will be excerpting from some of our favorite books of the year and giving readers the chance to win a copy. Follow along by visiting our master digital advent calendar, and use the hashtag #30DaysofGiving on social media for daily updates.

GARDEN FLORA by Noel Kingsbury (Day 21)

The following passage is excerpted from the book.

The History and Folklore of Four Festive Holiday Plants

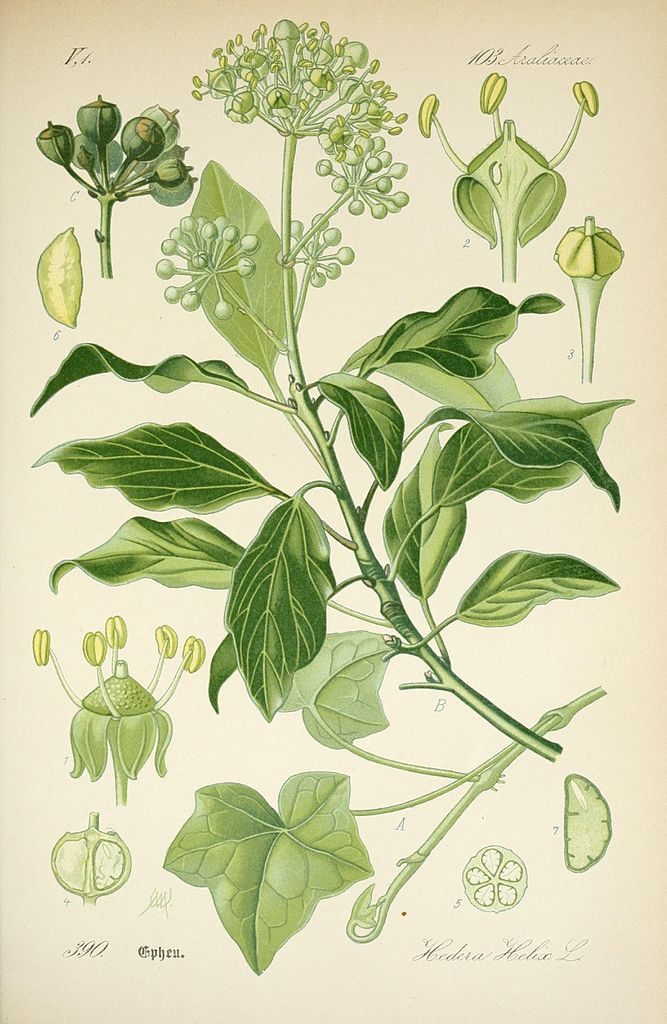

1. Hedera Araliaceae: Ivy

Photo © WikiCommons

Hedera (from the Latin for the plant) contains around 15 species. All ivies, as they are known, are evergreen woody climbers or ground creepers, from Eurasia and North Africa. They are distinctive for the aerial roots, which cling to tree trunks and buildings through a complex process, combining both physical and chemical ways of bonding. The plants climb until they can climb no more or they reach a certain maximum height, after which they become arborescent—no longer climbing, woodier, and with no aerial roots. Changes in leaf shape during the plant’s life is characteristic of Araliaceae; in the arborescent phase, ivy leaves develop a simpler shape. Ivies are generally to be found, and successfully grown, in climates that do not have severe winters or drought. They play an important ecological role in woodland, notably for providing generous nectar for pollinators and habitat for invertebrates and birds; in North America, however, ivies are potentially very damaging to forest floor plant communities, as they can form a suffocating monoculture. The damage that ivy supposedly does to trees and buildings is the subject of much discussion. The consensus is that it impacts negatively only on older and declining trees, which are losing their canopy, so allowing light to reach the ivy; an exception is that healthy conifers with an open canopy can be stressed by ivy growth, which adds to wind rock. On buildings, good maintenance is certainly required to limit the growth of ivy, but it can add appreciably to insulation.

Traditionally associated with Bacchus, the Roman god of wine, ivy was long used to advertise inns. There was also something of an association with death in European cultures, and being evergreen gets it noticed at Christmas. Historically there has been some medical use, and it is occasionally used as emergency animal fodder, although it is toxic in large doses. The plant has an undeserved reputation for the degree of its toxicity, partly because of confusion with the North American poison ivy, a totally unrelated and clearly very different plant, even to the extent that British schoolchildren refer to Hedera helix (English ivy) as “poison ivy”—an example perhaps of the overpowering strength of American popular culture.

Evergreen, easy to grow, and flexible, ivy was a decorative boon to our ancestors, its uses shaped over time by prevailing garden fashion. During the great era of the formal garden, from the 17th to the early 18th century, ivy was trained and clipped this way and that, as standards, and over all sorts of frameworks; and then with the advent of the naturalistic “English landscape,” it became invaluable for letting rip on ruins to make them more romantic and “picturesque”—no grotto or hermitage was complete without it. Ivy’s heyday was the Victorian era, its colour appealing to the dour aesthetic of the time, and its ability to cope with air pollution a definite plus. Numerous books suggested how it could be used as a houseplant, trained over bowers in the drawing room, up pillars, around fireplaces, etc. Vast numbers of potted plants trained up columns or over trellises were on sale in the markets, enabling almost instant effects to be created, inside or out. A particular Victorian favourite, and one perhaps worth reviving, is the “fedge,” where ivy is grown up a fence—I have seen this done over a substantial metal gate, so making a fedge that can be swung open.

A variegated ivy—which according to Pliny the Elder was carried as decoration in a victory parade by Alexander’s army in the 4th century BC—is the first known record of a variegated plant in the West. Ivies were taken to North America in the 18th century and became popular, especially to give an air of antiquity to buildings, which would hint at Old World respectability (as in “Ivy League” universities). Other species (e.g., Hedera colchica and H. canariensis) were introduced in the 19th century. Variable at the best of times, variegated sports or forms with novel leaf forms were selected and propagated, so that Shirley Hibberd (1872) could record 200 in his monograph on the genus. More recently, the realisation that the plant can become invasive has limited its popularity: Portland, Oregon, even has its own No Ivy League (est. 1994).

2. Helleborus Ranunculaceae: Christmas Rose

Hellebores wilt notoriously rapidly when cut but keep well when cut close to the flower base and floated in water. This method is even used when exhibiting the flowers at competitive shows. Photo © Noel Kingsbury

Sixteen perennial species are found from southern China across to northwestern Europe, with a centre of diversity in southeastern Europe. It is difficult to define species, and levels of natural variation are high. The name is from the Greek for another poisonous plant, probably Veratrum. Two growth-form categories are recognised. Caulescent species (e.g., Helleborus foetidus) develop a semi-woody stem, several being usually produced annually; these tend to be non-clonal and can be short-lived plants. Acaulescent species have leaves that spring up directly from the crown of the plant; they are clonal and long-lived but spread very slowly. The most prominent feature of the flowers are the sepals, which function as petals; the petals themselves evolved into nectaries, special structures at the base of the sepals which hold the nectar.

Hellebores are plants of mature woodland, wherever light levels allow, and woodland edge habitats. As many gardeners realise, they seed profusely; in the wild this is probably a means by which a rare event creating disturbance and increased light at ground level, such as a tree falling, is then exploited—with seed germinating en masse, leading to a new population, which may then survive for decades beneath younger trees. The plants contain a number of ranunculins, irritant and toxic chemicals that discourage animal predation and possibly infection by microorganisms.

Hellebores were used as an oracle flower in Medieval Europe, with 12 buds being put into water on Christmas night, each one representing a month, so that the next morning the open buds would predict good weather, the closed bad. The species best known to our ancestors, Helleborus niger (Christmas rose), was used in early modern Europe as a treatment for a variety of conditions; overdosing however could be lethal. It had many mythological associations, particularly with the curing of mental illness. Greek collectors were said to have not dug the plant up without first ritually circling it with a sword, while reciting prayers to the appropriate gods.

According to German botanist Otto Brunfels (1488–1534), hellebores were even then well known in gardens. In the mid-19th century, breeders in Germany began to create hybrids, largely between different forms of the very variable Helleborus orientalis. Nursery catalogues of the time list almost all the coloured and spotted variants available today. Further genetic variation was added when plants from the Caucasus came to Germany, via the St. Petersburg Botanical Garden. The first forms of H. orientalis came to Britain at around the same time, when a number of amateur breeders exchanged plants and seeds, creating around 50 selections by the 1880s. In 1890 Victor Schiffner of Prague University published the first book on the genus, Monographia Hellebororum.

Ashwood Nurseries in the English Midlands is one of the global leaders in hellebore breeding. This is their stock plant nursery, where painstaking hand-pollination every spring is used to continually improve the seed strains that are used to produce their plants. Photo © Noel Kingsbury

Interest in breeding slumped during the 1920s, and much was lost in World War II; Helleborus niger survived best, becoming the most commonly available species for some decades afterwards. One postwar English grower became obsessed with hellebores, however: Helen Ballard (1908–1995) taught herself German so that she could research the genus. Her breeding very much revived the plant in Britain. In her old age she sent some of her plants to Germany, where Gisela Schmiemann continued her work; seed was then distributed to Japan, Australia, New Zealand, and the United States. Hellebores were introduced to the United States in the 18th century, but breeding did not begin there until the mid-20th century; interest in the plants has since grown in concert with the rise of interest in them in Europe.

Several German breeders, notably Heinz Klose and Günther Jürgl, produced the first doubles in the 1980s. In England, Eric Smith and Jim Archibald worked on them in the 1960s, while Elizabeth Strangman played a key role in developing the modern range of hybrids. Today, John Massey’s range has a particularly high profile; he prefers to develop seed strains with a higher level of consistency than named cultivars—this makes sense, as vegetative propagation is painfully slow and expensive.

3. Ilex Aquifoliaceae: Holly

Photo © WikiCommons

There are around 400 species of holly: trees, shrubs, and woody climbers. The genus (named after the Greek for the evergreen holm oak, Quercus ilex) dates back to the Paleocene; it diversified before the continents parted, and then died out in many places, leading to a highly disjunct distribution—there are many species in the Americas, particularly the tropics, and in Southeast Asia down to New Guinea, but only one in Africa and one in Europe. In New Zealand, hollies are known only as fossils. Hollies tend to be stress-tolerant plants, the fact that most are evergreen making them effective at making the most of life as understorey beneath taller species. The flowers are very attractive to pollinators, often enticing them away from showier flowers in the vicinity. The fruit tends to be poor quality and consequently very persistent, which makes them useful for gardeners and as famine-food for birds at the very end of the winter.

Ilex aquifolium has been extensively used across Eurasia and the Middle East since ancient times for decoration at winter festivals; the Romans used it to celebrate Saturnalia. There are major links with pagan beliefs in Europe, but usually these are given a Christian veneer. It has been much used in folk-divination and healing rituals, which perhaps is behind the very wide range of superstitions around the plant, for example about when it could be brought into the house and when it should be removed; by the mid-19th century, however, consumer culture was overtaking folk beliefs, and it was estimated that around a quarter of a million branches of holly were being sold annually for Christmas in London. In Europe, I. aquifolium had a surprising use historically as animal fodder, as it has some of the highest calorie and nutrient count of any forage. Spineless or young growth was favoured, and its survival and spread in pastureland was often encouraged. The wood could be used for a number of specialist purposes, while birdlime was made from a mucilaginous material obtained from the bark.

Herbal uses involving holly berries or bark are various. Among some Native American communities, Ilex vomitoria (yaupon) was used for ritual purgings; today it is sometimes consumed as a herb tea, as it is a stimulant. Many species in the Americas served as herbal medical treatments, particularly in treating fevers. The stimulant tea, maté, of South America is also a holly, I. paraguariensis. Selection of distinct varieties for fruiting quality, fruit colour, and leaf colour and shape began in the 19th century. The gene pool of evergreen varieties is still dominated by Ilex aquifolium. The deciduous hollies are mainly grown for their spectacular and very persistent fruit; there has been much North American varietal selection and hybridisation between I. decidua, I. verticillata, and a number of others. Commercial production of both evergreen and deciduous hollies is as much for the floristry market as it is for the nursery trade.

In Japan, Ilex serrata has a long history in cultivation, but cultivars were usually given new names when introduced to the West, so their origin is obscure; this species has also been very popular for bonsai. Ilex crenata was also grown extensively in Japan, with many cultivars being produced during the Edo period; it was heavily promoted by the Arnold Arboretum in the 1930s and is now well established in cultivation, becoming especially popular from the 1990s onwards as a replacement for disease-hit boxwood.

4. Euphorbia Euphorbiaceae: Poinsettia

“In spring, [Euphorbia pilosa] and E. amygdaloides are attractive by their yellow flowers when little else is in bloom, but they are scarcely worth growing in a general way.” —Robinson, 1921

The name honors Euphorbus, a physician in North Africa in Classical antiquity who was noted for his contributions to natural history, including notes on these plants. With around 2,000 members, Euphorbia is among the largest genera of flowering plants, with species varying from small trees and shrubs through to perennials and annuals. Distribution is worldwide. There is a strong tendency for euphorbias to flourish in dry places, with around half having a distinctly xerophytic character. Some African species are an interesting example of parallel evolution, as at first sight they look just like cacti. The hardy species grown ornamentally are all members of the subgenus Esula, the least evolved of four subgenera, with a centre of diversity in the Mediterranean region. These tend to come from drier habitats, from rocky slopes to seasonally dry woodland. Nearly all are clonal perennials with competitive and stress-tolerant characteristics, with some exhibiting guerrilla spread, the rate of which can vary greatly between species. The wellknown Mediterranean-origin Euphorbia characias is interesting on two points: one that it is a rare example of a cultivated herbaceous plant which is effectively evergreen, as new stems replace the old ones just as they are dying in an annual cyle; the other is that it is non-clonal and short-lived, with a distinct pioneer character. Euphorbia is the only genus to have all three photosynthetic pathways: CAM, C3, and C4.

Euphorbias have a unique flower structure—stripped down to a bare minimum, but with some new structures added—an evolutionary one-off so surprising that looking into a euphorbia flower can be a disorienting experience. Male and female flowers are separate, with the male reduced to little more than one stamen, the female to a style with three fused carpels, each of which is capable of producing a seed. These parts are each enclosed in a cup-like cyathium, which is a completely novel structure unique to the genus. There are nectar glands at the base of this and then some cyathium “leaves,” which in turn are surrounded by bracts (modified leaves). The latter two sets of structures give the “flower” its colour—nearly always yellowy in hardy species but often red in those from warmer climates, such as Euphorbia pulcherrima (poinsettia).

A milky, acrid, latex-like sap is common to the whole genus and a potent deterrent to predators—smaller ones get their mouth-parts glued together and larger ones get burnt. Humans vary in the sensitivity of their skin, but great care must always be taken to avoid getting it into the eyes, as extreme pain and temporary blindness may result. The chemically complex and toxic sap of Euphorbia lathyrus (molewort) can be used to burn off warts and moles (and it follows that the common name has led to the myth that growing it deters garden moles). In 20th-century Mexico, E. antisyphilitica (candelilla) was used to produce a wax that served various purposes, e.g., waterproofing and polishing, but has largely been replaced by petroleum-based (and probably safer) alternatives; its scientific name indicates a former use in herbal medicine—probably highly risky!

Of all our contemporary perennial garden flora, this is the last major addition; the Robinson quotation well indicates that the appeal of the genus is historically quite recent. Euphorbia lathyrus has been known since the Medieval period. Records of E. myrsinites and E. epithymoides (as E. polychroma) appear somewhat later. Silva-Tarouca mentions several, as does Robinson. The plants stayed overwhelmingly in botanical and enthusiasts’ gardens until the 1950s, when E. characias and E. epithymoides led the field in making their way into gardens. It is probably significant that the widely read garden columnist Margery Fish wrote about euphorbias in the 1960s; the plants she discusses are very much the ones available today, plus a few new faces such as E. schillingii (from Nepal, 1975) and a growing range of E. characias cultivars.

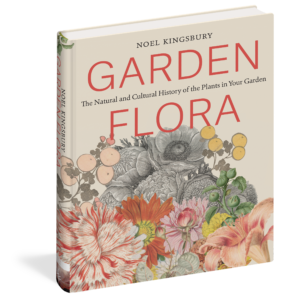

About the Book:

About the Book:

“A beautifully illustrated reference book covers the origins, ecology and history of popular garden plants.” —Shelf Awareness

The oldest rose fossil was found in Colorado and dates to 35 million years ago. Marigolds, infamous for their ability to self-seed, are named for an Etruscan god who sprang from a ploughed field. And daffodils—an icon of spring—were introduced to Britain by the Romans more than 2,000 years ago. Every garden plant has an origination story, and Garden Flora, by noted garden designer Noel Kingsbury, shares them in a beautifully compelling way. This lushly illustrated survey of 133 of the most commonly grown plants explains where each plant came from and the journey it took into home gardens. Kingsbury tells intriguing tales of the most important plant hunters, breeders, and gardeners throughout history, and explores the unexpected ways plants have been used. Richly illustrated with an eclectic mix of new and historical photos, botanical art, and vintage seed packets and catalogs, Garden Florais a must-have reference for every gardener and plant lover.

Buy the Book

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

Still need help finding a gift? Message our Holiday Hotline for personalized suggestions.

No Comments