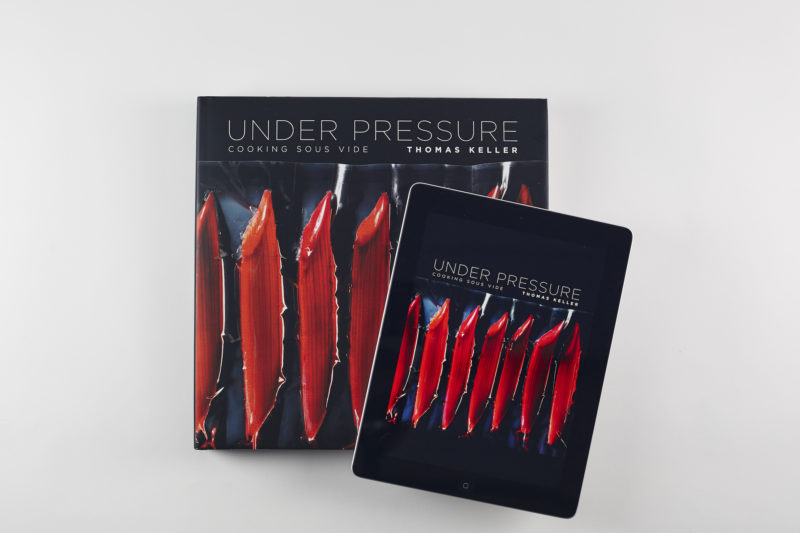

The Thomas Keller Library—comprising The French Laundry, Bouchon, Under Pressure, Ad Hoc at Home, and Bouchon Bakery—is available in all ebook formats for the very first time. To celebrate the digital publication of these cookbooks, every week we will highlight a different recipe and excerpt from each of the five books. This week, we’re highlighting Under Pressure.

Sous vide is the culinary innovation that has everyone in the food world talking. In this revolutionary new cookbook, Thomas Keller, America’s most respected chef, explains why this foolproof technique, which involves cooking at precise temperatures below simmering, yields results that other culinary methods cannot. For the first time, one can achieve short ribs that are meltingly tender even when cooked medium rare. Fish, which has a small window of doneness, is easier to finesse, and shellfish stays succulent no matter how long it’s been on the stove. Fruit and vegetables benefit, too, retaining color and flavor while undergoing remarkable transformations in texture.

In the section below, excerpted from Under Pressure, Keller introduces the basic principles of this revolutionary cooking method.

My Three Basic Principles of Sous Vide

Three basic principles govern sous vide cooking: pressure, temperature, and time.

Pressure

Pressure is determined by the power of the vacuum packer. The vacuum packer extracts air from the sous vide bag, squeezing the bag tightly against the food, sometimes even compressing the food. The questions to ask in order to determine the desired pressure are these: Do you want the item sealed very, very tightly or even compressed? Or is the item so delicate that it will be crushed by too much pressure? Is there a bone that might puncture the bag if too much pressure is used?

Chamber vacuum packers typically have one gauge for the amount of pressure and a second gauge for the duration of packing. Because vacuum-packing machines vary, general settings for packing are recommended (low, medium, and high) in the recipes here. Many factors determine the appropriate pressure; sealing time is determined by the thickness of the bag. The gauge on the packing bar records how hot it gets. Thicker bags need more heat to fuse completely.

For hard items, such as carrots, we want high pressure so that oxygen is removed and the plastic is as tight against the vegetable as possible, resulting in the maximum surface area coming into contact with the water’s heat. The need for maximum surface area is true for meat as well, but sealing pressure may vary depending on how delicate the cut is. For items we want to compress, such as porous fruits and vegetables, we also use high pressure. We compress melon to transform its texture and intensify its color. For some dishes, we compress two different proteins together (ham and mackerel, for instance; or chicken thigh and a farce, or stuffing; or layers of rabbit and bacon), not to change their shape and texture but to ensure that they bond as tightly as possible. For items such as a delicate piece of fish, we use less pressure so that we don’t bruise them; if you’re cooking a medallion of cod, you don’t want to flatten it out.

It’s also essential to keep in mind that the food must be cold when it’s packed and sealed. This is far more important than most people realize. In fact, Bruno Goussault says that when he trains chefs in sous vide technique, the number one error they make is not chilling the food properly before it’s sealed. The problem is related to the fact that in very low pressure situations, water vaporizes at a lower temperature. To demonstrate, Goussault will put one pan of cold water and another one of warm water in a vacuum chamber. When the chamber is locked and the vacuum turned on, the warm water will begin to boil vigorously almost immediately, as the water vaporizes. When warm food is put in a vacuum, the same vaporization will happen, drying it out and affecting its texture.

This is why, in addition to safety issues, when one of these recipes calls for a piece of meat to be seared before it is cooked sous vide, it must be thoroughly chilled for several hours, or overnight, before sealing it. If you don’t have the refrigerator space to allow the meat to cool uncovered, put the meat in a ziplock bag and submerge it in an ice bath until it’s thoroughly chilled before packing—below 6°C (42.8°F).

Temperature

The temperatures used in sous vide cooking are always below that of simmering water, which is about 87° to 93°C (190° to 200°F). The highest temperature we use, almost without exception, is 85°C (185°F), and this is exclusively for vegetables. Plant cell walls are weakened at this temperature, and so the vegetable becomes tender.

Meat and fish cooking temperatures are more varied. Fish proteins generally are delicate, and they denature and coagulate—that is, cook—at about 6.6°C (11.9°F) lower than meat proteins do. For meat, the cells begin to contract and thus squeeze out water and become tough at about 60°C (140°F). At about 70°C (160°F), the meat will have squeezed out much of its moisture, but the cells are easier to pull apart and the collagen will have begun to melt into gelatin (resulting in the very tender meat we expect from a braise).

Cooking a braise cut sous vide at 65.5°C (150°F) for a longer time, however, serves to break down the collagen without squeezing out all the juices, resulting in meat that is as tender as that from a traditional braise but more flavorful.

For tender breasts of poularde, we use 62°C (143.6°F), but we cook the thighs at 64°C (147.2°F). We cook delicate fish, such as St. Peter’s (John Dory), at 60°C (140°F).

These temperatures are basic guidelines, not hard-and-fast rules. They may vary slightly depending on how the food is to be treated before and after it goes into the bag. A chicken breast that will be seared after it’s removed from the bag may be cooked at a lower temperature than a breast that will simply be cooked sous vide, then sliced and served.

Time

In conventional cooking, timing can be thought of in terms not of how long to cook something, but of how long before you must stop its cooking. And this is tricky in conventional cooking, because you’re usually using temperatures far higher than the one you want the food to reach. If you’re sautéing a medallion of beef, for example, you may want the internal temperature to reach only 54.4°C (130°F), but you’re cooking it at about 200°C (400°F). That means that once the beef is at just the right temperature, the window of time you have to get it out of the heat is very small. Further complicating matters is the fact that the temperature of the food will rise at least a few degrees after it’s out of the heat, an effect called carryover cooking.

In sous vide cooking, however, once the food reaches the desired internal temperature, it stays there, even when left in the water. And there is no carryover cooking when the food is removed from the water.

This does not mean, however, that the window of time for perfectly cooked food is unlimited. If the meat spends too long in the heat, the color won’t change, but the texture and feel will—so it may look beautifully rare but the taste and texture will not be what you expect. It is meat that is rare yet overcooked.

Sirloin of Prime Beef

No Comments