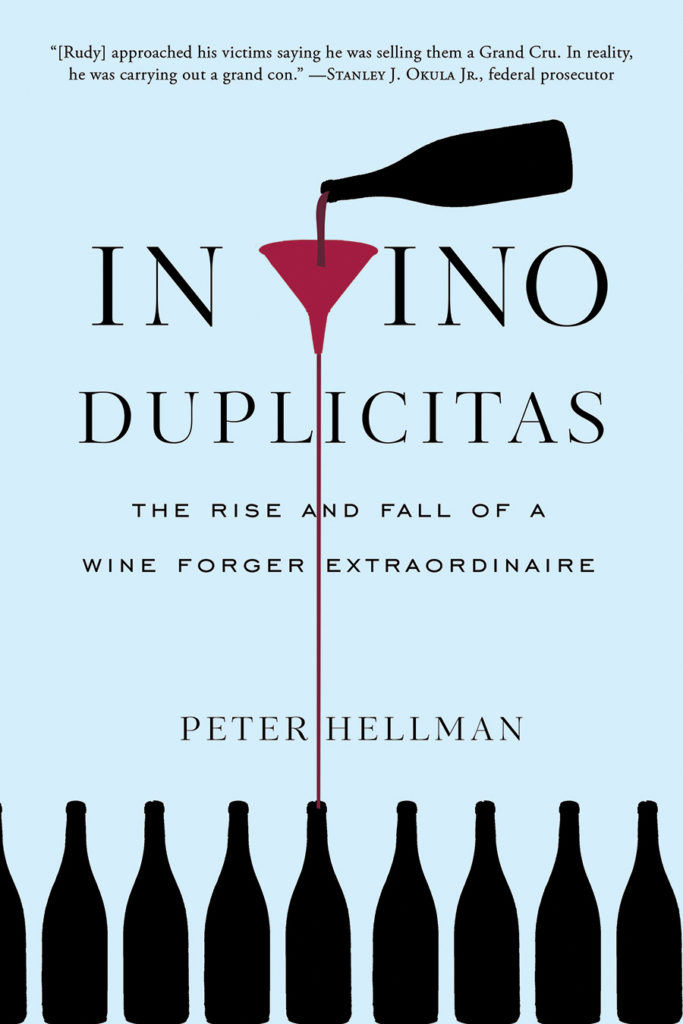

We’re so excited to share an excerpt of Peter Hellman’s In Vino Duplicitas, the story of Rudy Kurniawan, a 20-something Indonesian immigrant who rides his gift for tasting wine to the highest reaches of society—and then comes crashing down.

Chapter 1: Becoming Dr. Conti

A camera recorded Rudy Kurniawan, twenty-six years old but looking young enough to be carded, as he attended a Christie’s wine auction in Los Angeles, a catalog of fancy wines in his lap. The rare Asian among older white males, he wore a caramel-colored leather jacket, zipped up almost to the neck. His straight black hair is of modest length, and his sideburns just brush his ears. His eyes are dark and sharp behind black-rimmed eyeglasses. The auctioneer had just gaveled down a prize lot of wine that might have been made many decades ago by a callus-handed French farmer who would have been gratified to get a buck per bottle. In this year of 2003, somebody in this room had just bought it for thousands of dollars.

Kurniawan turned to the person on his left. “Dude,” he said, “I drank that wine on Thursday night. Now I feel bad. Can I refill the bottle and put the cork back in?”

Kurniawan flashed a smile and chuckled to himself.

Seekers of pulse-quickening wine often come by their passion not gradually but by epiphany. At a certain moment, the contents of their glass whisper intimacies straight to their soul. Most likely, the transformative wine is well-aged bordeaux or burgundy. In Kurniawan’s case, he claimed it was a “cult” Napa Valley cabernet sauvignon called Opus One, vintage 1996. To qualify as cult, a wine needs to be ultra-ripe, ultra-high-priced, and, because demand often exceeds supply, a bitch to acquire. If you want it direct from the winery, you may have to go on a waiting list—or even go on a waiting list to get on the waiting list.

A Wine Spectator review written four years after the vintage described 1996 Opus One as “bold, rich, and leathery, delivering tiers of currant, mineral, spice and sage.” Kurniawan ordered the bottle in 1999 or 2000, so the story goes, at a family dinner to mark the birthday of his father, who was visiting from Indonesia. They were gathered at a restaurant at Fisherman’s Wharf in San Francisco, but when asked in 2006 for the restaurant’s name by a Los Angeles Times reporter, Kurniawan could not remember, despite boasting a guillotine-sharp memory for any experience connected to wine. Released at $125, 1996 Opus One was probably double that price or more on the restaurant’s wine list.

Something about that bottle clicked open a previously inactive sensory circuit in Kurniawan. Wasting no time, he embarked on an informal crash course, learning all he could about wine. He began to show up at wine tastings at shops in and around Los Angeles. A refreshingly young entrant into an older crowd’s game, he was high-spirited and able to turn on strong emotional connectivity in others.

Because Indonesians of Chinese ethnicity are scarce at West Coast rare wine tastings, Kurniawan was easy to notice and remember. Tapping into a shadowy family fortune, he bought a bounty of very expensive wine. His corkscrew was hyperactive. Elite Napa Valley reds, like that Opus One, came first on his shopping list. The more difficult they were to get, the more eagerly Kurniawan sought them. He also fancied muscle-flexing, amped-up Australian reds. As is common with wine novitiates, it was that wallop of flavor rather than a caress that he was looking for.

Kurniawan sped on to high-end bordeaux, then began a deep engagement with the intricacies of burgundy. In those early days, he was buying copiously from Woodland Hills Wine Company, a shop with a deep inventory of high-end wine located in the San Fernando Valley. Kyle Smith, whose family owned the shop, invited Kurniawan to become a member of a tasting group of burgundy buffs calling themselves Burgwhores. They were tasting wines at price points that required wealth, and Kurniawan seemed to have it. Being a member of Burgwhores gave Kurniawan entrée to a world where he quickly rose to a starring role. It wasn’t only that he stepped up with trophy bottles. He had a puppy-dog talent for charming his fellow Burgwhores. Where he and his money came from, nobody knew. He was a one-off.

What he tasted, he precisely remembered. If the wine was a multi-grape blend, he seemed to be able to pick out each variety by its character. In his classic The Taste of Wine, Émile Peynaud suggested a simple way to explain the difference between average wine tasters and the truly gifted. It’s done by analogy to what the ear hears: Go to a room adjoining one where people are gathered and hold up a fine crystal wineglass. Strike the edge of the bowl with a fingernail or a spoon so that it pings. In the other room, the least sensitive listener hears only an unknown sound. One level up, a more discerning listener identifies the sound as the pleasurable ping of crystal. The gifted listener, hearing the same ping, says, “That vibration corresponds to the note E.”

She has perfect pitch. Kurniawan has it for wine.

***

More books have been written about wine than about home gardening. Wine newbies often try to learn more by reading about it. Kurniawan, too, opened books, and he sucked knowledge from more experienced tasters. First and foremost, however, he educated himself by incessantly tasting. Émile Peynaud argued that to be successful the taster must “proceed by intuition . . . without the aid of reasoning.” With this approach, “the study of details and deductions aren’t necessary. Contact with the organs of smell and taste alone suffice to. . . unveil [a wine’s] identity. Either we get it right away, or we don’t.” To get it right away was Kurniawan’s gift. “I’ve seen Rudy nail ten out of twelve burgundies that he tasted blind,” the wine auctioneer John Kapon of Acker Merrall & Condit tells me. Rajat Parr, a San Francisco sommelier and winemaker, says that after observing Kurniawan at a tasting, “I was very, very impressed. He identified most of the wines blind.” Jefery Levy, a film producer and screenwriter who drank with Kurniawan (and spent two Christmas Eves with Kurniawan and his mother), says flatly of his friend’s tasting savvy, “He was almost always extremely, unbelievably, insanely correct.”

So correct that Levy became suspicious. Kurniawan was pulling off his tasting feats at restaurant wine dinners. Was he “flipping somebody in the kitchen a thousand bucks” to tip him off on what wines were being poured supposedly blind? Levy decided to test Kurniawan at his own home, where he could set up a foolproof blind tasting. “I tried to trick him in all sorts of crazy ways. I served him wines from Bordeaux, Burgundy, Italy, Spain, California. Either he would get the country, the year, the maker, or he would get very close.” Reaching for an explanation of Kurniawan’s tasting chops, Levy references method acting: “It’s about sense memory,” says Levy. “You try to get emotions going based on memories in your life. Rudy had a sense memory, but it had to do with his nose and taste buds.”

Levy calls Kurniawan a wine “savant.” He could remember individual wines in the way Dustin Hoffman’s “Rain Man” could account for every card in a deck at a Las Vegas poker table. Étienne de Montille, a winemaker from Volnay who knew Kurniawan, calls him a “UFO.” Being perceived as both a savant and a UFO could only be helpful to Kurniawan when he trotted out unicorn-rare bottles. Had he lacked those qualities, people might have had more suspicions about him and the source of his wines.

Kurniawan declared himself a guardian of authenticity. He boasted a sharp eye for tiny details on the label, branding on the cork, or neck capsule of a trophy bottle confirming that the wine within was real or gave it away as a fake. He told the British wine writer Jancis Robinson, “When I go to restaurants and drink great wines, I’m very careful to ensure that the empty bottles are trashed and the labels are marked so they can’t be reused.” The opposite was true: Rudy was very careful to ensure that empties were returned to him with labels unmarked.

In the end, it was his imprecise knowledge of a particular domaine’s history that tripped him up. It happened amid extreme merriment, one spring evening, in New York.

The mistakes that he made, minuscule and highly arcane, upended his life. Also upended would be the practices and pleasures of seekers after rare old wine.

To learn more about how Rudy Kurniawan went on from that first sip of wine to pulling off the largest wine con in history, get your copy of In Vino Duplicitas.

Buy the Book

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

No Comments