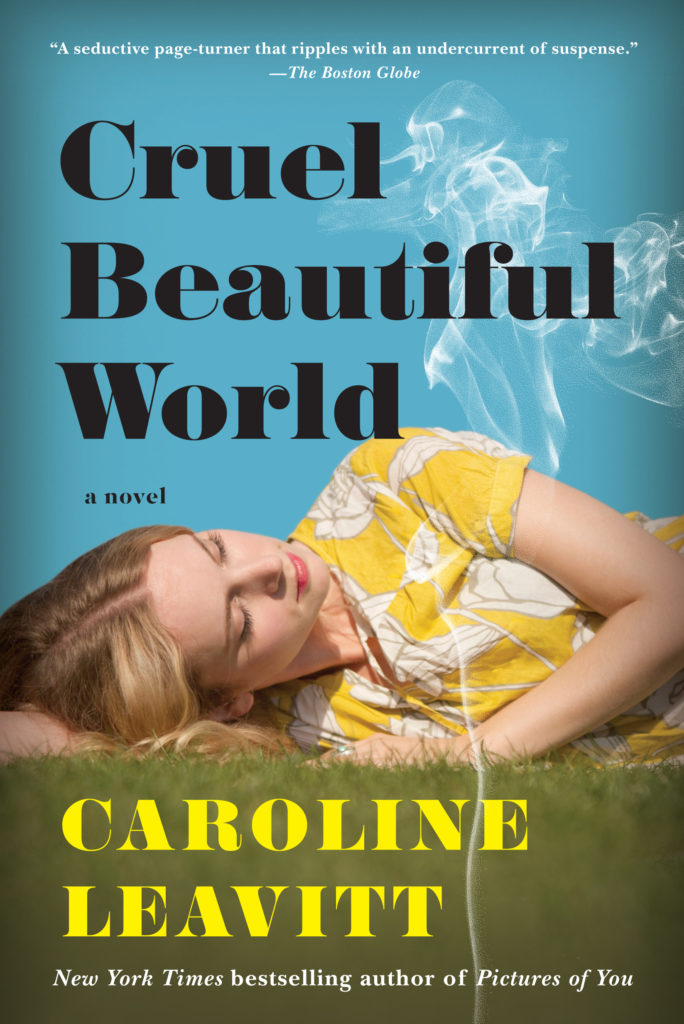

Welcome to our #FridayReads feature on the blog, where we’ll be excerpting a chapter of one of our favorite books to start your weekend. This week, it’s Caroline Leavitt’s Cruel Beautiful World, a mesmerizing novel against a backdrop of peace, love, and the Manson murders.

Scroll down for an excerpt.

Cruel Beautiful World

1969

Lucy runs away with her high school teacher, William, on a Friday, the last day of school, a June morning shiny with heat. She’s downstairs in the kitchen, and Iris has the TV on. The weather guy, his skin golden as a cashew, is smiling about power outages, urging the elderly and the sick to stay inside, his voice sliding like a trombone, and as soon as she hears the word elderly, Lucy glances uneasily at Iris.

“He doesn’t mean me, honey,” Iris says mildly, putting more bacon to snap in the pan. “I’m perfectly fine.”

Good, Lucy thinks, good, because it makes it that much easier for her to do what she’s going to do. Lucy is terrified, but she acts as if everything is ordinary. She eats the bacon, the triangles of rye toast and scrambled eggs that Iris leaves her, freckling them with pepper and pushing the lumpy curds around her plate. Lucy drinks the orange juice Iris pours for her and picks up the square multivitamin next to her plate, pretending to swallow it, but then spitting it out in her napkin moments later because it has this silt-like under-taste. She wants to tell Iris to take more vitamins, since she won’t be around to remind her. It’s nearly impossible for her to believe that Iris turned seventy-nine in May. Everyone always says Iris barely looks in her late sixties, and just last week Lucy spotted an old man giving Iris the once-over at a restaurant, his eyes drifting over her body, lingering on her legs. Lucy knows three kids at school whose parents–far younger than Iris–have died suddenly: two fathers felled by heart attacks, a mother suffering a stroke while walking the dog. Lucy knows that anything can happen and age is the hand at your back, giving you an extra push toward the abyss.

She tells herself Iris will be fine. Iris hasn’t had to work for years, since receiving sizable insurance money from her husband, who died in his sixties. Plus, she has money from Lucy’s parents. Lucy had never heard her parents talk about Iris, but Iris told Lucy and Charlotte it was because she was only very distantly related.

Lucy was only five when her parents died, Charlotte a year and a half older, and she doesn’t remember much about that life, though she’s seen the photos, two big red albums Iris keeps on a high shelf. She’s in more of the photos with her parents than Charlotte is, and she wonders if that’s because, like now, Charlotte doesn’t like being photographed. There are lots of photos of Charlotte and Lucy together, jumping rope, sitting in a circle of dolls, laughing. But the photos of her parents alone! Her mother, winking into the camera, is all banana blonde in a printed dress, her legs long and lean as a colt’s. Her father, burly and dark, with a mustache so thick it looks like a scrub brush, is kissing her mother’s cheek. They hold hands in the pictures. They smooch over a Thanksgiving turkey. They were at a supper club, dancing and having dinner, the girls at home with a sitter, when the fire broke out. Later, the news reports said it was someone’s cigarette igniting a curtain into flames so heavy, most of the people there never made it out.

When she thinks about her parents, Lucy feels like there is a mosquito trapped and buzzing in her body. She tells herself the stories Charlotte has told her, the few Charlotte can remember. There was the time their parents took them to Cape Cod and they rode ponies on the beach. The time they all went to New York City to look at the Christmas lights and Lucy cried because the multitude of Santa Clauses confused her. She has told herself all these stories so many times, she can almost convince herself that she really remembers them. Iris has no stories about the girls’ parents. “Our lives were all so busy,” Iris says. “We just never got together.”

Lucy glances at Iris bustling about the kitchen, pouring coffee, reaching for the sugar. She looks old, her skin lined, her hands embroidered with blue veins. Iris had never seemed old before, Lucy thinks. Iris took the girls to the park, she threw and sometimes caught Frisbees. The only thing she couldn’t do was take the girls to a movie in the evening because she didn’t like driving at night. Plus, she preferred to go to bed early. Charlotte was always Iris’ “big girl helper”, watching Lucy on the swings, running after her, and a lot of the times, just sitting on one of the benches with Iris, the two of them with their heads dipped together, laughing, so that Lucy would have to stand on the swings and go higher just to blot out the surprise of being the odd person out.

Iris turns the TV to another channel. She shakes her head when she sees the hippies on the news, a sudden influx of them congregated and camping out in Boston Common, spread out on the green lawn like wildflowers, all of them in tie-dyes and striped or polka dotted pants, some of the girls in flowing dresses or minis so tiny they barely cover their thighs, and bare feet, but Lucy finds herself glued to the set. “Like sheep!” Iris says, pointing to the way the cops are herding the kids back onto the streets. ”Look at how they dress!” Iris marvels.

Lucy sighs. Iris wears jewel-tone silk dresses every day, or blouses and skirts. She’s always in low heeled strappy shoes. Her white hair is braided into a fussy ring around her head, like Heidi, and her earrings are always button ones, instead of the long, jangly ones Lucy wears. “Look at that one,” Iris says, when the camera focuses on a boy with ringlets skimming his shoulders. “What a world,” Iris marvels and shuts the set off. But Lucy loves the way the hippies look, the multitude of rings on their toes and fingers, the clashing clothes. These kids are part of a life glittering just inches away from her and all she has to do is grab hold, the way she does with William’s hair, thick and shiny as satin. She can almost feel her hands in it, tugging him closer to kiss her.

She wants to tell Iris and Charlotte. She wants to tell someone, but she can’t.

Iris hands Lucy a brown paper bag filled with a peanut butter sandwich and an apple, the same lunch Lucy’s had since elementary school. Iris sits down and pulls out the crossword puzzle from the daily newspaper. This is her favorite part of the day. She picks up a pencil and chews on the end and then glances at Lucy again. “Honey, go find a hairbrush before you go,” Iris says.

Lucy pats down her cap of platinum curls, and then sits and finishes her juice. She looks around the kitchen as if she’s memorizing every detail–the oak table and chairs, the braided rug, because until she’s 18, just two years from now, when no one can legally stop her from being with William, she won’t see this room again.

Hooked? You can buy the book here.

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

No Comments