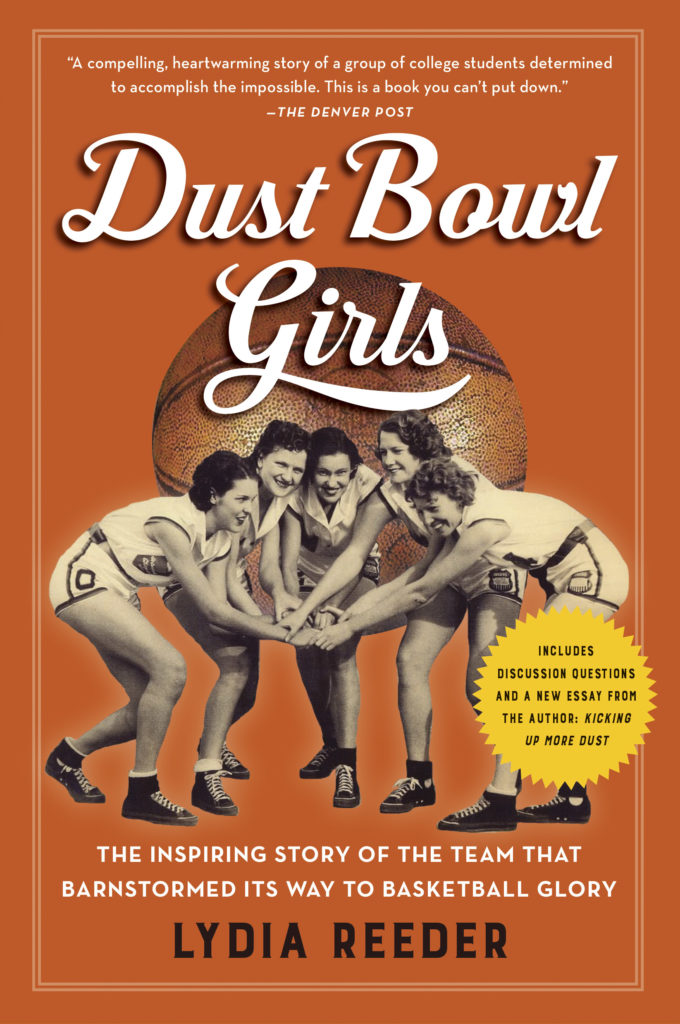

Welcome to our #FridayReads feature on the blog, where we’ll be excerpting a chapter of one of our favorite books to start your weekend. This week, it’s Lydia Reeder’s Dust Bowl Girls, the thrilling true story of a depression-era championship women’s basketball team (think The Boys in the Boat meets A League of Their Own).

Scroll down for an excerpt.

New Recruit: Chapter 1

February 1930

Doll Harris crouched in ready position, took a deep breath, and focused on the basketball now in enemy territory. More than anything, she wanted the ball back. Doll’s high school team, the Cement Lady Bulldogs, was battling its archrival, the Fletcher Lady Wildcats, for the Southwest Oklahoma district championship and the right to play in the regional tournament. Doll was a senior and the Bulldogs’ star forward. The game, in its final seconds, was tied, 28–28. The hometown crowd of 350 leaped to their feet when the Bulldog guards fought hard for the ball, the rubber soles of their Converse high-tops rendering sharp chirps with every move. The referee, expecting the tangle of players to commit a foul at any minute, held his whistle ready.

“Get the ball to Doll, you all,” the pep squad chanted.

“Ball to Doll!” the crowd joined in.

With twelve seconds left in the game, Doll and her teammates did the drill that would set up the final shot. The Cement forwards passed the ball to each other, keeping it in play to run down the clock. The frustrated Wildcat guards couldn’t get their hands back on the ball. Finally, with three seconds left, Doll jumped to catch a wild pass from her teammate. With one second left, she made the shot. As if answering a magnetic call from the basket, the ball whooshed cleanly through the net. Cement had won, 30–28.

Cheers shook the gymnasium’s rafter bolts. Farmers, ranchers, oil-rig workers, and their families who attended all the games leaped skyward. Schoolkids hugged each other, and the heroic Lady Bulldogs, still feeling the effects of the adrenaline rush, danced in circles while holding hands. A unifying spirit took hold, driving away thoughts about the plummeting crop prices, rising foreclosures, and growing food scarcity. These worries evaporated in the warmth spread by the delight in winning.

After more than fifteen minutes, the jubilant shouts dwindled to buzzing murmurs, and the boys began warming up on court for the next game. The crowd settled in to root for their team one more time.

Doll was on her way back to the locker room when she heard someone call her name. She glanced back to see her coach, Mr. Daily, motioning her over to where he was standing with a broad-shouldered man wearing a black suit and a silk tie. He stuck out like a sore thumb in the midst of all the people milling about in work overalls and cotton dresses. As she walked back toward them, the stranger fixed his collar and smoothed a hand down the front of his jacket. Mr. Daily introduced the well-dressed man as Sam Babb, coach of the Cardinals at the Oklahoma.

Presbyterian College for Girls in Durant, 150 miles east of Cement. Doll lifted her eyebrows and stared at Mr. Babb. His thick black hair was cut in a flattop above a high forehead and bushy eyebrows. He had a broad, stern face; a straight nose; and a prominent chin that turned double when he stared down at her. She never would have guessed he was a basketball coach. He looked more like a banker from the city. And she knew all she needed to know about bankers—her father, a sharecropper, hated them because they were always raising interest rates. As Babb took a couple of steps toward her, she noticed that he had a pronounced limp.

Babb greeted Doll in a smooth baritone voice. When he reached out to shake her hand, his solemn face lit up with a smile. He said he’d like to tell her about the basketball program at OPC, that he was looking for a talented forward to add to the Cardinals’ offense.

“I need players willing to work hard. Are you willing to work, Miss Harris?”

“I’m a competitor.”

“But are you a team player?”

“I can be a team player.”

“Good girl. Then I am prepared to offer you financial aid.”

“Financial aid? To play basketball?”

“Yes, it would pay for your education.”

Doll’s jaw dropped, and she looked at Babb in disbelief. Being offered the chance to attend college and play basketball was a dream come true. For the past couple of years, Doll could never stop thinking about being recruited by a women’s industrial team like the Dr Pepper girls in Oklahoma City or, even better, the Dallas Sunoco Oilers, last year’s national champions. These big companies hired the best coaches and players to work in the factory and play basketball at night and on weekends. Winning sports teams generated lots of good publicity.

Thousands of screaming fans flocked to their games, and ever since she was a kid playing on a homemade dirt court with a peach-basket goal, Doll had dreamed of glory.

Her heart pounded so hard, she thought it might just launch itself right out of her chest. Maybe this wasn’t playing for an industrial basketball team, but in a way, it was even better because she’d be able to go to college, too. She folded her arms, leaned back on her right leg, and began to tap her left toe out of sheer excitement.

“Doll, listen to Mr. Babb,” said Mr. Daily, putting a hand on her shoulder to calm her fidgeting.

“Yes, sir.” She inhaled a deep breath.

For several minutes, Babb continued telling her about OPC, a women’s college, but housed on a campus where poor Indian kids also went to elementary and high school, paid for by the Presbyterian Church, of course. “OPC is nationally accredited, one of the best in the region, known for its quality of higher education,” he said. Then he told her he wanted to meet with her parents, the next day if possible.

“Meet my folks?” Doll’s voice cracked when she spoke.

“Is something wrong?” Babb said.

Yes, there was something wrong. While Doll was listening to Mr. Babb, thoughts of home began to percolate at the back of her mind. She saw the pail she used to milk the cow every morning, sitting in its corner in the barn, made of galvanized metal so heavy she couldn’t lift it and had to drag it along the ground when she was a little kid. Her sister Verdie’s long auburn hair braided with wild honeysuckle. The desperate look on her father’s lean, tanned face when he told his family last October that because of drought, the wheat crop had shriveled to dust. Her shock when she found out that her parents quit eating the eggs from their chickens, selling them instead so that Doll could have new basketball shoes. She and her sister sometimes went without eating meat and eggs, too. Sinking into these thoughts, she stopped breathing—she knew she could never leave Caddo County.

The Great Depression was under way, and poverty lived like a king in western Oklahoma. Months of dry weather had lifted the crops right out of the ground as if the hand of God (or the devil) had pulled up row upon row of every corn, wheat, or cotton plant, exposing the roots and killing them. Fields and pastures had turned dead brown and seemed to rise on the wind like spirits yearning toward heaven, filling the air, sometimes, with sand storms and suffocating grime. Money for food and clothing was scarce. Many families ate what they could grow and supplemented that with what little they could hunt for. Where drought was worst, they gathered weeds—dandelions, sheep sorrel, and lamb’s quarters—and ate them steamed with canned beans and lard. Squirrel hunting became an art. The hunter would scope out a squirrel’s nest high in a cottonwood. Then he, or she, would lie on the ground and face the sky with a .22 rifle pointing at the nest in its sights. Sometimes they’d wait an hour or more for the squirrel to show its eyes. Squirrel gravy on eggs was considered a delicacy.

But not all was tragic in these wide-open spaces. Country girls like Doll grew up surrounded by endless acres of crops; pasture; and wild, open plains. They ran footraces with coyotes and horses, crawled effortlessly across the wooden beams holding up barn roofs, and created secret tunnels with hay bales. They played alone and with brothers, sisters, cousins, and friends. At night, the stars glistened a brilliant, bleached white in an immense black sky. The only noises were crickets and wind.

Doll couldn’t leave her life on the farm. Everyone depended on her. She’d marry a farmer or an oil-rig worker like her sister did and have children of her own. But she also couldn’t disappoint Mr. Daily, who had arranged for Mr. Babb to watch her play. So she said, “No, nothing’s wrong. Come by tomorrow morning, early.” And then she gave Mr. Babb directions to her home.

Hooked? You can buy the book (now available in paperback).

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

No Comments