Passage excerpted from Marta McDowell’s The World of Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Buy the Book

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

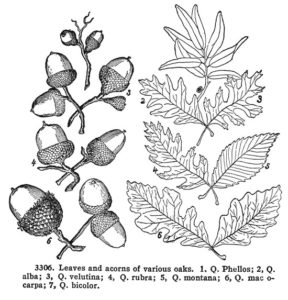

Oaks, botanically Quercus, are familiar trees across North America. Shown here are the acorns and leaves of six species of American oak.

North and east of Pepin, the mix of trees changed to the boreal forest that sweeps far into Canada. Here the conifers—pine, tamarack, and spruce—go to the front of the class, along with birch, beech and maple. So when the Ingallses drove north to Grandpa Ingalls’s farm for maple sugaring in late winter, their journey followed the actual distribution of tree species in the woods.

The woods were a dark place in summer, as the canopy closed in when the trees leafed out. The wild things that inhabited the woods were not magical beasts, but carnivores—panthers and wolves and bears (oh my!)—and the herbivores they fed on—rabbits, deer, and muskrats. Pa hunted, loading his rifle with homemade bullets. There were tracks in the snow and the shrieks in the night. Between actual bears and bear-shaped stumps, it must have seemed a growling, howling wilderness.

While Pa hunted, farmed, and fished, the distaff side of the family tended to the house, laundry, poultry, dairy, and garden. The Ingalls garden was fenced and close to the house. Given the needs of the family and the harvest that Laura remembered, it must have been an ample plot. The brindle bulldog, Jack, patrolled at night to keep the garden deer-free, becoming the hero of every gardener who battles Bambi and her lot. With the exception of the heavy digging, Ma, Mary, and Laura handled the garden chores.

By Helen Sewell. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers. Please note: “Little House” ® is a registered trademark of HarperCollins Publishers, Inc.

A word of warning. If you spend any time comparing the Little House books with Wilder’s autobiography Pioneer Girl, you may be tempted to ask “Will the real Laura Ingalls Wilder please stand up?” It turns out that with a close reading of the latter, the first vegetable garden mentioned in the series was planted not by Laura’s parents, but by interim owners of the log cabin. The Ingallses lived in the little house in Wisconsin not once but twice, with Kansas, the Indian Territory of Little House on the Prairie, sandwiched in between. It is a reminder that while fact-based, Wilder’s work is fiction. The character Laura is sometimes different from the real Laura, like Peter Pan and his shadow, although readers know in their hearts that the Laura on the page and the Laura who was a person have the same character, the same values. The sometimes-blurred line between fact and fiction adds texture to the tale of Laura Ingalls Wilder.

Regardless, the vegetable garden behind the log cabin was the first to appear in the series and, we suppose, the first she remembered. It isn’t surprising what bubbled up as Laura’s garden recollections: weeding—not every child’s favorite part of growing vegetables—and harvesting, which is much more fun. While collecting the dusty potatoes that Pa had dug sounds vaguely mundane, Laura’s description of pulling the skinny carrots and the round turnips from their underground homes is rousing. The girls helped carry the root crops back underground, “down cellar,” as she later calls it, for careful storage in bins and barrels. With the night temperatures taking a dive, the cellar with its insulation of earth-controlled humidity and temperature kept the vegetables viable. The dried leaves and straw that Pa banked around the exterior foundation would have helped too. And Caroline Ingalls would have checked the stored vegetables regularly all winter to guard against rot and to parcel out the supply to make it last until spring.

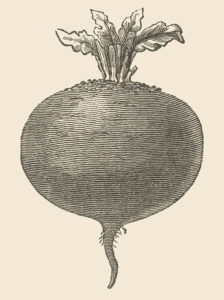

Laura wrote about the energy-packed beet, a vegetable that has been a part of American gardens since colonial days.

Like the settlers flooding into Wisconsin during the Ingallses’ day, many of the vegetables harvested from their garden were European migrants. Beets, for example, originated as wild plants that grew on the sand and rocky shingle around the temperate coastlines of the Mediterranean. An almost four thousand-year-old cuneiform tablet in Yale University’s collection includes a Babylonian recipe for broth made from beets. Ancients cultivated them for the leaves, and these ancestral beets looked more like chard—a close relative. Root beets came somewhat later, during the Roman era, selected and bred to favor swollen, nutritious roots. By the 1650s, beets had made it to the Plymouth Colony, along with Laura’s forebears. Governor William Bradford inscribed this vegetative verse in 1654, capturing the beet for posterity:

All sorts of roots and herbs in gardens grow,

Parsnips, carrots, turnips, or what you’ll sow,

Onions, melons, cucumbers, radishes,

Skirrets, beets, coleworts, and fair cabbages.

(Skirret, a relative of the carrot, was a popular root vegetable in England and its colonies, but was supplanted by the prolific and easier-to-prepare potato. Colewort was a name applied to leaf, as opposed to head, cabbage. Collards are a modern approximation.) While the beets that Laura and Mary helped harvest went to cool storage in the cellar, other produce was lugged to the attic. Braids of onions and strings of red peppers festooned the rafters. The pumpkins and their squash kin, including the thick-skinned Hubbards, furnished a winter playroom for Laura and Mary, at least until Ma cooked them. The attic, while still cold, would have been a bit warmer and drier than the cellar, thanks to heat rising from the stove and radiating from the chimney. Winter nights Pa banked the fire in the cookstove, gathering the hot coals, compacting the heat, maybe adding a green log. He covered the embers with ash so that that fire would burn low, smoldering till sunrise.

The attic was also the storehouse for culinary and medicinal herbs, making the space fragrant as well as burgeoning. It is disappointing—at least to a garden writer—not to find an itemized list of herbs in Wilder’s novels…

An attic hung with herbs and onions and furnished with winter squash made a perfect playroom. 1953 by Garth Williams, renewed 1981 by Garth Williams. Used by permission of HarperCollins Publishers.

No Comments