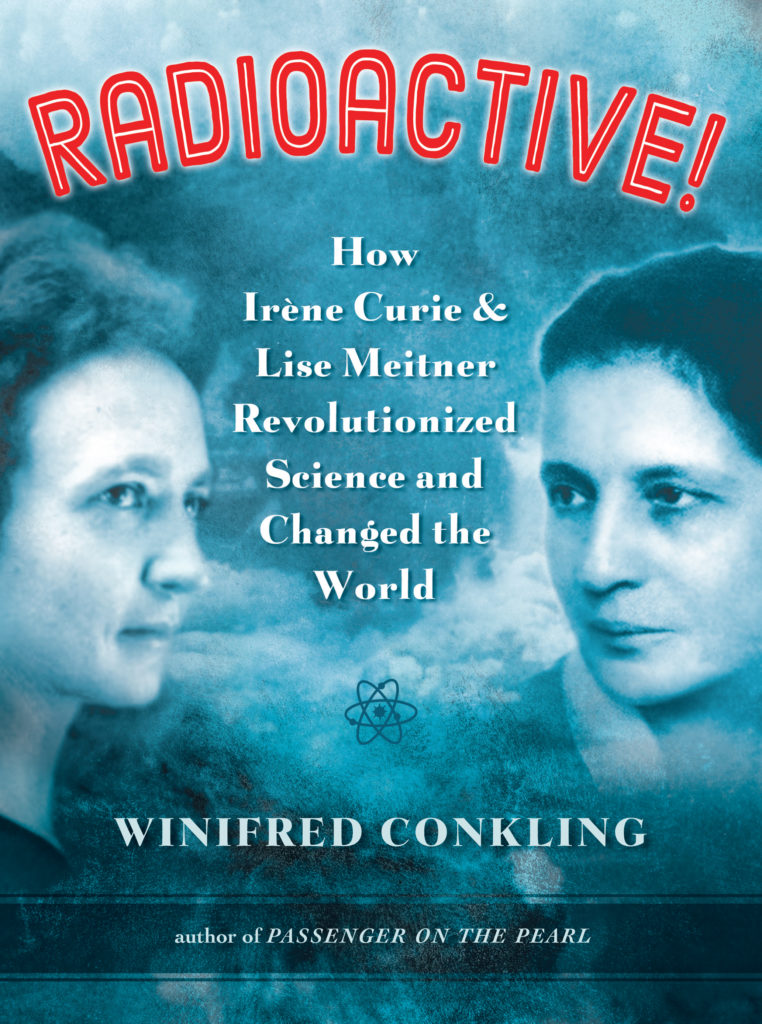

Winifred Conkling’s Radioactive! presents the fascinating, little-known story of how two brilliant female physicists’ groundbreaking discoveries led to the creation of the atomic bomb.

In 1934, Irène Curie, working with her husband and fellow scientist, Frederic Joliot, made a discovery that would change the world: artificial radioactivity. This breakthrough allowed scientists to modify elements and create new ones by altering the structure of atoms. Four years later, Curie’s breakthrough led physicist Lise Meitner to a brilliant leap of understanding that unlocked the secret of nuclear fission. Meitner’s unique insight was critical to the revolution in science that led to nuclear energy and the race to build the atom bomb, yet her achievement was left unrecognized by the Nobel committee in favor of that of her male colleague. Radioactive! presents the story of two women breaking ground in a male-dominated field, scientists still largely unknown despite their crucial contributions to cutting-edge research, in a nonfiction narrative that reads with the suspense of a thriller.

Hooked? You can order the book here:

Indiebound | B&N | Amazon | Workman

Scroll down for an excerpt from the book.

In a Man’s World

In 1909, two years after Meitner began working in the basement laboratory, Prussia opened its universities to women. At that point, Fischer allowed Meitner to enter the rest of the building and visit the upstairs labs for the first time. (He even installed a toilet for her.) He recognized Meitner’s brilliance and her impeccable work ethic, and he became one of her strongest supporters.

Other men in the laboratory, however, never got used to the idea of having a woman in the lab. When Meitner and Hahn walked together in the street, Fischer’s young male assistants greeted him with “Good day, Herr Hahn,” intentionally ignoring Meitner. She never responded to the insults.

Meitner also encountered prejudice from men in other related fields. An encyclopedia editor liked one of her articles so much that he asked “Herr Meitner” to write more. When he learned that “Herr Meitner” was actually “Fraülein Meitner,” the editor wrote back to say that he would not dream of publishing anything written by a woman!

Sometimes scientists in other labs did not realize Meitner was a woman. When Ernest Rutherford, a physicist from New Zealand, visited Berlin, Hahn brought him to Meitner’s downstairs laboratory to meet her. When he shook her hand, Rutherford said: “Oh, I thought you were a man!” Meitner found the remark amusing. Her only frustration came later when the men stayed behind to discuss their research on radioactivity and she was expected to take Mrs. Rutherford out Christmas shopping.

Meitner was always very generous about giving Hahn credit for work that she could have published on her own. Working by herself, Meitner discovered that radioactive thorium decayed into a substance she called “thorium D.” A well-known professional recommended that she publish the results by herself and Hahn agreed, but she submitted the article as a team with both their names anyway. “He was much better known than I,” she later explained.

In the early years, when it came time for them to announce their research findings, Meitner always insisted that Hahn present their work. She was shy and an inexperienced speaker. They were the same age, but because of her educational delay, Hahn had considerably more professional experience and confidence.

Sometimes friends asked why Meitner and Hahn did not marry each other. When asked, Meitner said: “Oh, my dear, I just didn’t have enough time for that!” Hahn explained:

There was no question of any closer relationship between us outside the laboratory. Lise Meitner had had a strict, lady- like upbringing and was very reserved, even shy. I used to lunch with my colleague Franz Fischer almost every day and go to the café with him on Wednesdays, but for many years I never had a meal with Lise Meitner except on special occasions. Nor did we ever go for a walk together. Apart from the physics colloquia that we attended, we met only in the carpenter’s shop. There we generally worked until nearly eight in the evening . . . One or the other of us would have to go out to buy salami or cheese before the shops shut at that hour. We never ate our cold supper together there. Lise Meitner went home alone, and so did I. And yet we were really very close friends.

The work Meitner did with Hahn was unpaid, yet as long as she was working in a lab, Meitner was unlikely to find a husband willing and able to over her financial support. Instead, she continued to rely on an allowance from her father as her sole source of income.

Though Meitner never married, she had a number of close friendships that endured her entire life. She was a devoted and loyal friend, who found the most significant meaning and satisfaction in her work. This period of intellectual and creative freedom brought her joy and genuine personal fulfillment.

No Comments