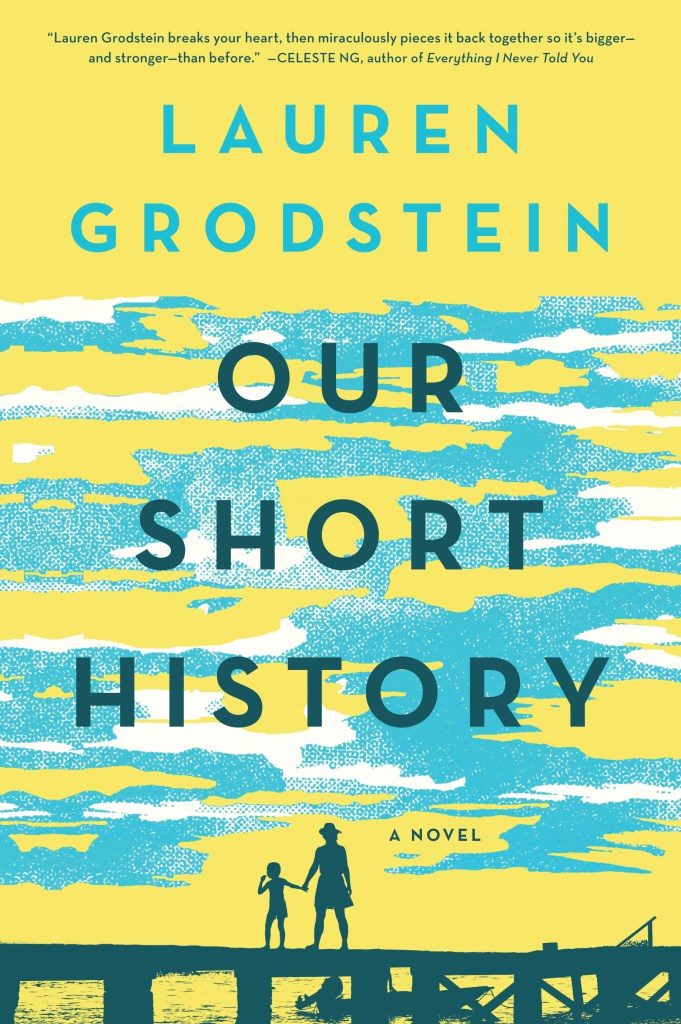

Welcome to our #FridayReads feature on the blog, where we’ll be excerpting a chapter of one of our favorite books to start your weekend. This week, it’s Lauren Grodstein’s unforgettable novel about parenthood, sacrifice, and life itself, Our Short History.

To learn more about Algonquin’s All Summer Long reading campaign (and to enter to win amazing books and a limited-edition tote bag throughout the summer), click here.

Scroll down for an excerpt.

Our Short History

When I was a kid, not much older than you, I was certain I’d grow up to be a writer. I had a portable typewriter—my dad bought it for me at a garage sale—and late at night, when everyone else was asleep, I’d sit in the kitchen and painstakingly type out little scenes and scraps of fiction. I liked mystery stories a lot, suspense, moments of horror and surprising redemption. I hoped one day to write something about the Holocaust, but give it a happy ending. This was when I was a teenager and thought I could rewrite any script.

Now I’m grown and know that very few of us get to become the people we thought we’d be when we were kids. I never did write a novel, is what I’m saying, or even a decent short story, although I found other successes and pleasures in life and don’t regret most of the things I haven’t done. That said, I still have time, Jake, and I still like putting down words on paper. So I’ve decided to write a book for you, with chapters, a title, maybe even an appendix of photographs. It seems like the right way to tell you everything I want you to know. And this island, my sister’s guesthouse, the cloudy Northwest: it’s all very conducive to writing. I have a comfortable chair here and a shiny new laptop. And there’s so much I want to tell you.

As of course you know, this island where my sister lives with her family—Mercer Island—is all pine trees and lacrosse fields and half-caff americanos. You can see the churning waters of Lake Washington from every direction, usually iron gray but sometimes unaccountably blue. Seattle lies a few miles to the west. I’ve always thought it was peaceful here, and good for us, although I do miss our home in Manhattan. (Remember how you used to ask if we could build a tunnel from West Seventy-Fourth Street to Mercer Island? And because I thought I had all the time in the world, I used to say, maybe later?)

This will be a wonderful place for you to do the bulk of your growing up, after you’ve moved here for good. You’ll have your cousins to hang out with, and your aunt Allie to make sure you eat your vegetables. And your uncle Bruce is one of the most senior people at Starbucks, which means that living here you’ll be very nicely provided for. You’ll ski at Whistler and spend Christmas in Hawaii and pass long summer weekends at the family estate in Friday Harbor. You’ll learn to drive and then you’ll get a car.

That said, I’ve instructed Allison to send you to one of the public schools on the island instead of the private cloister where she sends her own kids. Public school matters to me; I want you to know how the real world lives, or what passes for the real world here on Mercer Island. I can’t bear the idea of you growing up amid all this privilege without some awareness that there are people who grow up on free lunch. Remember, Jacob, I spent my own childhood in a Long Island duplex, my father’s parents in the apartment upstairs. As I’ve told you a million times—as I hope you still remember—my mother was the fifth daughter of a Bronx postman. My father was the only child of Hungarian immigrants who barely survived World War II. Neither one of them grew up with anything like luxury, and neither did my sister or I.

Allison and I frequently discuss issues of privilege and economy. She says it doesn’t mean we have to raise our kids broke just because that’s how we grew up. She thinks that insecurity about money doesn’t necessarily make a person more empathetic or kind: sometimes it just makes a person nervous her whole life. And she’s right, I know she’s right, but still it irks me to think you’ll never understand that you are, in so many ways, so very lucky. Allison says, But in at least one way you aren’t lucky at all. None of us are. And money is no compensation.

There is no compensation. I am your only parent; I am forty-three years old; I have stage IV ovarian cancer. I have perhaps two or three years left in my life, and once I am gone you will move here, to Mercer Island, to live with my sister, Allison, and her family. You can bring your hamster and all your toys. You can bring anything you want. You know this, Jake. You know that if it were up to me, I would live forever with you in my arms.

This will be a strange exercise, this book, I can tell. As I type, I feel like I’m writing about someone else. Like this couldn’t be happening to me, or to us. And then—there—I feel the port between my ribs, and there it is again, the staggering truth.

I still haven’t decided how often I want you to think of me in the future, Jake, or what kind of memory I want to be. I mean, of course I want you to remember me—I want you to remember that I existed, and that I loved you, and that generally speaking we were pretty happy. But I don’t know if I want you to remember every single specific about our life together, so that your life on Mercer Island always feels like your “new” life, as though you’re comparing it to something that came before which was somehow truer. I want this to be your true life, and I want Allison and Bruce to be like your mother and father, and your cousins to be like your siblings, and for you to consider yourself one of theirs. I want them to be your soft place to land. This is, I think, the best thing a family can be.

But I also want you to remember days like last Monday, when I took you to the Woodland Park Zoo and we paid five dollars to feed a leaf to that giraffe and instead of eating the leaf the giraffe licked your hand with its prehensile tongue and you were so surprised you froze and she did it again. This time you shrieked and I shrieked too and then we laughed until we got the hiccups. The zookeeper said, I’ve never seen her do that before! You must be delicious. You blushed a bit and said, That’s what my mom thinks. That I’m delicious. And oh, how you are, Jacob. You, with your soft longish hair and your feathery eyelashes, you have no idea.

Sometimes I find myself daydreaming—sometimes in the middle of a conversation, even—and I realize I’m imagining what you’ll look like in a few years. Will your hair still curl around the edges? Will you still wear Derek Jeter T-shirts every day? Since you were a toddler you’ve been a New York Yankees fanatic, but then the other day I caught you in your cousin Dustin’s old Mariners jersey—I hadn’t done laundry in a while—and I thought, There it is, the beginning of a kid I’ll never know. The thought made me more curious than melancholy; I was like an anthropologist studying the future you. Your cousin Dustin was chasing you around the lawn while Allie yelled at both of you to come in for dinner, and I was just sitting on the dock, witnessing. Your life without me. Dr. Susan says this sort of witnessing is normal. This sort of floating away. You had a scrape on your shin I’d never noticed before.

“What time is it in New York, anyway, Mom?” you asked me at breakfast. I told you it was eleven, and you said that’s what you thought. You said, “In New York, it’s already the future.”

Jacob, I promise, if I do nothing else with the time I have left, I will write this book. I’m not sure of its title yet—do titles matter if you have only one reader?—but I know what I’m going to include: whatever wisdom I have, whatever lessons I’d pass on to you later, if I were going to be here later, when you were old enough to need them. My hope is that whenever you miss me or whenever you just want to know more about the person I was, you’ll be able to open this book and read these pages and remember me. Learn more about me. And that way, even though you won’t always be with me, I will always, at least a little, be with you.

I plan to be honest here. I plan to be excruciatingly, extraordinarily honest. I will not edit out the truth; I will not try to make myself look better than I really was. Than I really am. If I can’t tell you the truth, why should I tell you anything at all?

Hooked? You can buy the book here.

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

No Comments