In zero gravity, how do astronauts eat food?

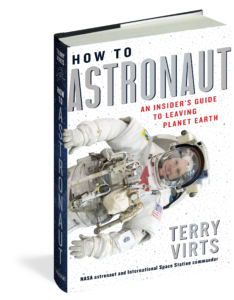

We all have questions about the details of spaceflight, and the reality of astronaut life is very mysterious to most of us. Not many people can answer the question of how astronauts eat food while in orbit from direct experience. Enter Terry Virts, a retired NASA astronaut, International Space Station commander, and colonel in the United States Air Force. His new book, How to Astronaut, an Insider’s Guide to Leaving Planet Earth, explains the ins and outs of life in space. This chapter on space cuisine has all the details of how astronauts eat food, complete with menus!

Excerpted from How to Astronaut, an Insider’s Guide to Leaving Planet Earth by Terry Virts. Copyright © 2020.

Just Add Water: Space Station Cuisine

As they say, “Keep the crew well fed and they can survive anything.” And I think they’re right. Any mission longer than a few hours should involve food, and if the food is good, the crew will be happy. If it’s not good, it’s going to be a long mission. This was true for both of my spaceflights, and I was a happy crewmember for my seven months in space.

The days of astronauts eating food paste from a tube are long gone. Even though we don’t exactly have Michelin-star cuisine in space, I found it to be good and a highlight of my missions. For that matter, how often do you eat in a Michelin-star restaurant on Earth? The most important thing for me, and for most of my colleagues, was variety. The second most important thing was having enough to eat. Doing two and a half hours of exercise every day in addition to being extremely busy meant that I was hungry and needed to eat. Thankfully, there was plenty of food for the whole crew, though there have been several missions during the ISS program when food started to get scarce because of resupply vehicle problems, and that led to some crew hunger.

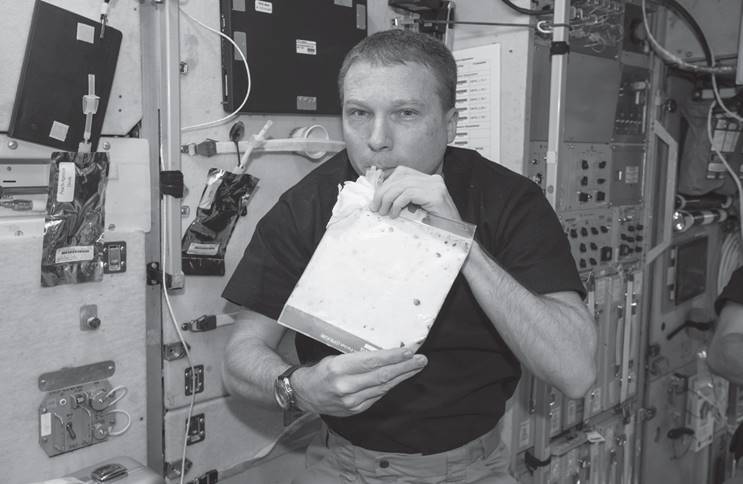

There are several categories of space food. The first is thermo-stabilized, which means it can last for months and is ready to eat without rehydration, like the MRE (military rations). This food came in green bags and included meat, vegetables, desserts, soups, etc. You simply opened the bag (reheated if desired), and it was ready to go. Another kind is rehydratable food. This type was lighter, smaller, hard, and crunchy and came in clear, see-through bags. You would plug it into a machine, select how many milliliters of water you wanted to add, press the blue (ambient temp) or red (hot water) button, unplug the food, spin it around like a centrifuge, mash the wet bag of food around for a minute, let it sit for ten minutes, and voila, food—meats, vegetables, fruits, desserts, basically anything that can be dehydrated. This food also tasted good, and it seemed fresher than the green-bag food. These two types were the bulk of my diet while on the ISS.

There was also off-the-shelf food: M&M’s (called “candy-coated chocolates” in NASA’s awkward alternative universe). Tuna fish in a bag.mSpicy olives. Chocolate-covered blueberries. Reese’s peanut butter cups. Power bars. You get the idea. Any food that can be purchased at the local grocery store, stay fresh for a few months, and be shipped “as is” to space can probably find its way onto a cargo manifest. In terms of bread, we have only tortillas on the American segment, because they can last a long time without spoiling or making crumbs like a normal loaf of bread would. Fresh fruits and vegetables, like oranges, carrots, and apples, are a welcome treat on newly arrived cargo ships. Oranges tended to rot pretty quickly, but they sure did smell good. It was always amazing to have fresh food after eating packaged food for months.

There were also drinks. Any type of drink that can be produced in powder form can become a space drink, including fruit juice (yes, it’s actually Tang), tea, coffee, milk, sports drinks, hot chocolate (in short supply and high demand), and even smoothies. There was a pretty good selection of everything other than carbonated drinks. I was a Diet Coke addict before my flight and was nervous about going without for half a year, so I requested tea, figuring that would be my caffeine drink. Unfortunately, after about three days of drinking tea I had had my fill. There were lots of varieties of tea: black tea, green tea, sweet tea, tea with lemon, etc. But the bitter taste was too much. It was great once every few days, but not every day.

The vast majority of our food was organized in BOBs (NASA acronym for food bag) that each contained eight days of that particular category of food for the whole crew. They are fairly dense containers, the size of a backpack, and are organized by type of food—meat, vegetables, desserts, drinks, fruits/nuts, breakfast, etc. The contents are part of a standard menu of food, which is selected to appeal to most astronauts. We were supposed to go eight days between new BOBs for most categories, though we would usually last longer than that.

Opening a new food container usually took about fifteen to twenty minutes by the time you went to find the new one and scanned it into the inventory management system, so it was always a bummer if you were the last person to finish off a BOB and had to go restock the cabinet. It was a job that we all shared, without formally being tasked; if we saw the need to open a new BOB, we would just do it. That attitude was very helpful for crew cohesion. If I saw a crewmate restocking food supplies and I had a minute, I would always stop and help out.

Beyond standard menu items that the whole crew shared, each of us was given nine personal bonus containers of food. These could be from the NASA, Russian, European, or Japanese menus or even items from the local grocery store. I picked mostly US, but also a few containers of Russian and European food. The key was variety. The Russians were particularly good at fish, mashed potatoes, and soup. Plus they had real bread—Borodinskiy khleb (бородинский xпеб, or Borodinsky bread), a dark rye sourdough that was basically the only bread I ate for 200 days. The only European food I was able to get was some leftovers from previous European astronauts. They had dishes made by real chefs, and those were always a treat.

We would also get care packages from Earth with each visiting cargo ship, usually containing beef jerky and chocolate candy. It was kind of funny because we were overrun with jerky, but for me the chocolate was most important. So when the Cygnus cargo ship blew up just before my launch, and with it one of my care packages full of Reese’s peanut butter cups, I was a little alarmed. Then, halfway through my mission, a Russian Progress cargo ship blew up, and along with it more chocolate. Our mission duration was then extended indefinitely as a result of that accident, and I had to start rationing my chocolate. It was painful. Our 169-day mission became a 200-day mission, and I literally ate my last Reese’s on flight day 200, hours before leaving space. I had barely made it. Our chocolate situation will likely go down in the annals of exploration history as a tale of stretching both rations and human endurance to their limits.

The food setup was a little different on the shuttle; there we chose every meal for the whole flight. It was a good system in that we ate what we wanted, but it made it less likely that you would try other food items. Like many astronauts my taste changed while in space, but the shuttle flight was so short and I was so busy that any lack of variety didn’t matter. At the end of STS-130, we left a huge bag of supplies on the station, including food, which was a morale booster for the ISS crew remaining behind.

One of my favorite food stories involves an experiment I did called Astro Palate. It was a psychology experiment designed to measure how food affects our mood. They had me eat bland food and then do certain mundane or unpopular tasks, like Saturday cleaning or repairing the toilet. Next week I would eat some of my favorite dishes and do the same tasks. Some weeks I would eat the food after doing the tasks. Then I took a survey of my mood both before and after the tasks. Sure enough, I was a lot happier after eating the good stuff. Samantha gave me endless grief about this experiment because while she was busy giving blood or doing other invasive medical tests, I was eating chocolate brownies after vacuuming filters. We laughed a lot about that, but I never felt badly about it. Unless I had to do the cleaning after eating cheese grits.

As you might imagine, there were some food items that weren’t favorites. I was lucky because my crew had pretty diverse tastes, and it would be a bummer if everyone wanted to eat the same food. However, a few things were always in demand—brisket, shrimp cocktail, chocolate brownies, scrambled eggs, sausage, hot chocolate, and, ironically, veggies. Nobody on my crew liked cheese grits or curried vegetables or most of the thousands of packets of tea. So I started a bag of uneaten food, a large bag of food items that the US segment crew (Americans and Samantha) didn’t want. Every few weeks the Russian cosmonauts would come down and raid that bag; they really enjoyed the food that we didn’t want. Conversely, we loved the extra items that they were tired of, especially canned fish. This system of sharing food worked great; everyone had good variety, nothing went to waste, and I don’t remember throwing away any food during my mission.

I was very thankful to the NASA, Russian, and European food labs for making some very good food for us. Between exercising two and a half hours a day and no fried fast food, I came back to Earth trim and in great shape. I still remember the first meal I ate back on the planet—one of my doctors went to the airport kiosk and got a chicken sandwich for me. The fresh bread and mayonnaise were absolutely amazing.

Even though our space food doesn’t compare to a freshly prepared meal here on Earth, some of my best memories in space occurred around the dining room table, food velcroed and duct-taped to the table, drinking from sealed metal bags, enjoying rehydrated vegetables and irradiated meat (2012 was a particularly good year for beef, apparently—they stamped the year on our meat bags, like a fine wine). I wouldn’t trade in my fine dining here on Earth, but I wouldn’t mind an occasional space food meal every now and then.

More How to Astronaut

“There’s something intriguing to be learned on practically every page… [How to Astronaut] captures the details of an extraordinary job and turns even the mundane aspects of space travel into something fascinating.”––Publishers Weekly

“There’s something intriguing to be learned on practically every page… [How to Astronaut] captures the details of an extraordinary job and turns even the mundane aspects of space travel into something fascinating.”––Publishers Weekly

Ride shotgun on a trip to space with astronaut Terry Virts. A born stroyteller with a gift for the surprising turn of phrase and eye for the perfect you-are-there details, he captures all the highs, lows, humor, and wonder of an experience few will ever know firsthand. Featuring stories covering survival training, space shuttle emergencies, bad bosses, the art of putting on a spacesuit, time travel, and much more!

Buy the Book

Bookshop | B&N | Amazon | Workman

No Comments