For most people in the world, the word “stout” applies to one beer: Guinness. In the long period of decline among the porters and stouts of England, Irish companies established their product as the stout. Beamish and Murphy’s, the two breweries of Cork, may not have achieved Guinness’s fame, but for over a century and a half, they’ve helped Dublin’s giant establish the dry stout (sometimes called Irish stout) as one of the world’s most durable and popular beers.

The standard product of these breweries is a paradoxical brew. On the one hand, it’s very thin and weak (about 4% ABV), no stronger than American light beer. On the other, it is brewed with acrid roasted barley and truckloads of hops, making it a sharp, bitter pour. And speaking of pour, the nitrogen that made Guinness famous livens most Irish stouts, abroad and in the U.S. (Trust Irish scientists to invent a nitrogenating “widget” that ensures each bottle and can results in a proper pint.)

An entirely different Irish stout is sometimes honored with its own category designation, yet the entire “style” is really defined by just a single brand. Few beers are as justifiably legendary as Guinness Foreign Extra Stout (“FES” to devotees), and few taste so vividly of the past. Guinness introduced this beer to the U.S. in 1817, though the recipe was different then. Typical of the era, the brewery aged some of its beer in large wooden vats and then blended a portion back into freshly made stout. Like London porters of old, that aged portion was inoculated with wild yeast and bacteria and grew acid over time. This was FES, and although the recipe has evolved thanks to the invention of black malts and the later inclusion of unmalted roast barley, it retained its character thanks to the huge vats still in use as late as the 1990s. The writer Michael Jackson visited then, reporting that aged, soured beer was still being blended in FES. The “lactic, winy” flavors came from “a blend of beers, one of which has been matured for up to three months in wooden tuns that are at least 100 years old.”

Curiously, Guinness is now hugely secretive about its process. When I spoke to master brewer Fergal Murray, he wouldn’t even acknowledge those lactic, winy flavors anymore. “Do you think it has those?” he asked coyly. He acknowledged that the pH was lower because of the roast barley, and “maybe those things are giving you, or the people out there in the world, that perception.” Tours are no longer given, even to journalists, and the company speaks only in general terms about their process, invoking the “unique mystery of Guinness.” He elaborated on that mystery, sort of. “There is a special brew that is separated in the brewery and goes via a variation in process times in brewhouse and in fermentation—which we use to enhance the flavor characteristics of Guinness. More taste. Only known to a few.”

Whatever the process, the result is one of the most intense beers on the market: a muscular 7.5% stout of great density and layered complexity. The black malts are charred and ashy, as bitter as French roast coffee but also tannic and dry. They would overwhelm the beer were it not for a latent acidity, which reins in the malt astringency and allows FES’s quieter flavors to emerge—chocolate, dark bread, grassy hopping.

(Copyright notes for pictures: O’Neill’s Pub photo by John Bradley (Own work) [CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons, Guinness Man (not required for use) by By Jon Sullivan [CC0], via Wikimedia Commons, Guinness Brewery (not required for use) By Ijanderson977 (Own work) [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons)

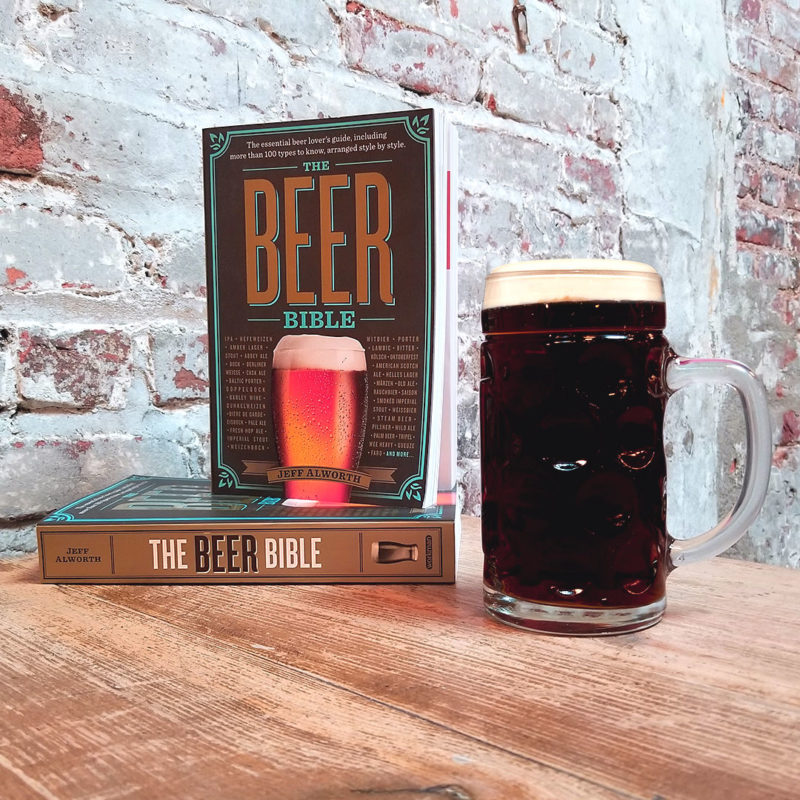

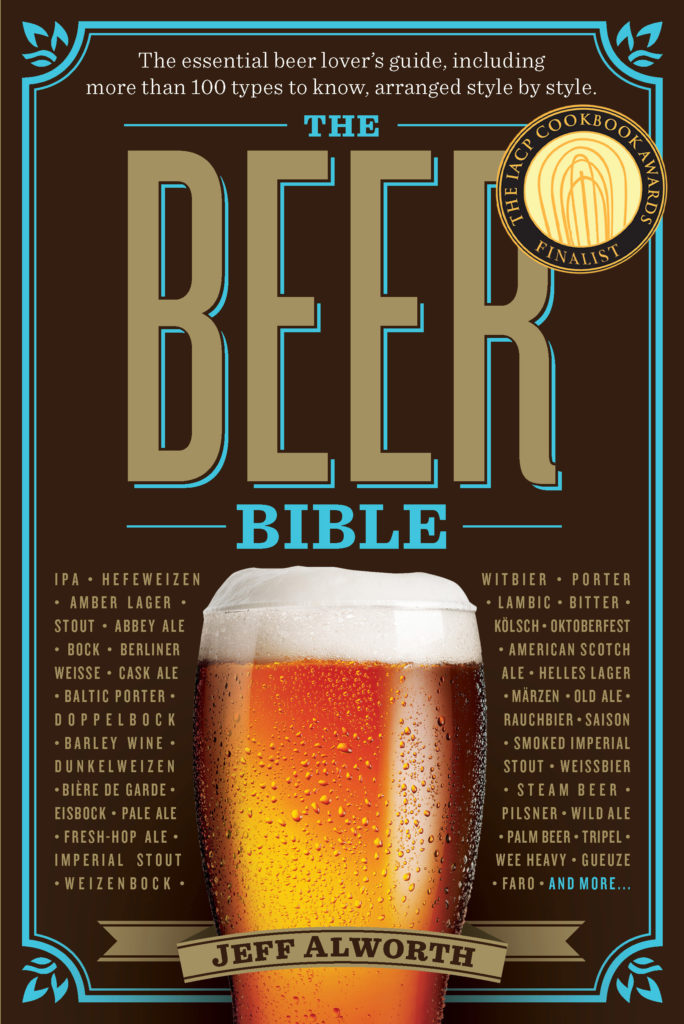

Excerpted from Jeff Alworth’s The Beer Bible

Don’t forget to check out the book!

About the Book:

About the Book:

The ultimate reader- and drinker-friendly guide to the world’s ales and beers, and the book that approaches the subject in the same way beer lovers do—by style, just like a welcoming pub menu. Divided into four major families—ales, lagers, wheat beers, and sour and wild ales—The Beer Bible covers everything a beer drinker wants to know about the hundreds of types of beers made, from bitters, sessions, and IPAs to weisses, wits, lambics, and more. Each style is a chapter unto itself, delving into origins, ingredients, description and characteristics, sub-styles, and tasting notes, and ending with a recommended list of the beers to know in each category. Infographic charts throughout make understanding the connection between styles and families immediately understandable. The book is written for passionate beginners, who will love its “if you like X, try Y” feature; for intermediate beer lovers eager to go deeper; and for true geeks, who will find new information on every page.

Buy the Book

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

No Comments