You may think your childhood home is “weird” because of your mom’s tchotchke obsession or your dad’s collection of Civil War memorabilia, but trust us, you haven’t seen weird until you’ve explored the world’s strangest homes and neighborhoods in Atlas Obscura, available now.

1. Shackleton’s Hut

CAPE ROYDS, ANTARCTICA

The shelves are lined with tins of curried rabbit, stewed kidneys, ox cheeks, and sheep tongues. Long johns hang off washing lines slung from the walls, and boots sit in rows underneath the makeshift beds built from wooden crates. Ernest Shackleton’s hut looks just as it did when the explorer abandoned it in 1909.

Shackleton and his team of 14 men assembled the prefabricated timber hut in February 1908, having lugged it from London via New Zealand. The building was to serve as a base during the Nimrod Expedition, Shackleton’s quest to be the first to reach the South Pole. The four-man trip toward the pole had a bittersweet outcome: with their ponies dead and their food supply dwindling, the quartet turned back 112 miles (180 km) from the South Pole—the closest anyone had gotten at the time.

The contents of Shackleton’s hut, naturally preserved in the frozen climate, offer a fascinating insight into the Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration, the era beginning in the late 19th century in which pioneering explorers like Shackleton, Scott, and Amundsen led perilous, often fatal expeditions. Among the items on his packing list, intended to sustain 15 men for up to two years, were 1,600 pounds of the “finest York hams,” 1,260 pounds of sardines, 1,470 pounds of tinned bacon, and 25 cases of whisky (that’s 726 kg, 572 kg, and 667 kg, respectively).

The discovery of this last item was the cause of much excitement when, in 2010, conservators retrieved a crate of Mackinlay whisky from a stash of booze hidden beneath the hut. Three of the bottles underwent chemical analysis in Scotland, after which Mackinlay used the flavor profile to create a replica whisky. The original bottles were returned to the hut, where they sit in tribute to a long-departed gentleman explorer.

Visitors to the hut must be accompanied by a guide. A maximum of 8 people are allowed inside at one time, and all are required to sign the logbook.

S 77.552922 E 166.168368

2. Paper House

ROCKPORT, MASSACHUSETTS, U.S.A.

The phrase “paper house” may invite images of something fragile, but the Paper House of Rockport has been standing strong since the 1920s. In 1922, mechanical engineer Elis F. Stenman started building a house with newspapers. Initially, it was a hobby. Stenman pressed the papers together to form the walls, and applied glue and varnish to make them sturdy.

When it came time to furnish the house, Stenman continued the newspaper theme, rolling papers into tiny logs, stacking them to form chairs, bookcases, and desks, and sloshing varnish on top for a lacquered wood effect.

Stenman spent summers in his newspaper house until 1930, after which the place opened to the public as a museum. Look through the layers of shellac and you’ll see headlines and tales from the 1920s, including, on one desk, accounts of Charles Lindbergh’s pioneering transatlantic flight.

52 Pigeon Hill Street, Rockport. The house is around 40 miles (64 km) northeast of Boston, in the coastal town of Rockport. It’s open from spring through fall.

N 42.672947 W 70.634617

3. Château Laroche

LOVELAND, OHIO, U.S.A.

Harry Andrews led a dramatic life. During his time as a World War I medic, Andrews contracted cerebrospinal meningitis at Fort Dix. Doctors pronounced him dead, but Andrews had other ideas. To their surprise he made a full recovery and got sent to work at Château Laroche, a French Renaissance castle that had been converted into a military hospital.

Château Laroche made such an impression on Andrews that, over a decade after the war ended, he set about constructing his own medieval castle in Loveland, Ohio. The determined veteran spent over 50 years hand-building his own Château Laroche on a plot of land beside the Little Miami River. By 1981, Andrews’s record-keeping showed that he had used 56,000 bucketfuls of stones from the river and 2,600 sacks of cement. (He made bricks by pouring the cement into molds made from milk cartons.)

Andrews died that year, aged ninety-one, in odd circumstances: He was incinerating trash at the castle when his pants caught fire, leading to severe burns that eventually killed him. With Andrews gone, the castle was bequeathed to his Boy Scout troop, the Knights of the Golden Trail. They still manage Château Laroche, its sword collection, and the surrounding gardens.

12025 Shore Drive, Loveland. The castle, located 25 miles (40 km) northeast of Cincinnati, is open daily from April to September and on weekends from October to March.

N 39.283520 W 84.265976

4. Garden of Eden

LUCAS, KANSAS, U.S.A.

After serving in the Civil War as a Union nurse, Samuel P. Dinsmoor settled in Lucas, Kansas. It was there, in 1905, that he began building his own patriotic Garden of Eden.

The centerpiece of the garden was a “log” cabin that Dinsmoor sculpted out of limestone. Around the cabin he built tall, thin cement sculptures reflecting his Populist politics, Biblical interests, and distrust of authority. Adam and Eve, Cain and Abel, and the devil all make an appearance, as do snakes, angels, and a waving American flag. The most blatant political commentary is found in the “Crucifixion of Labor,” a sculpture of a doctor, lawyer, banker, and preacher nailing a man labeled “Labor” to a cross.

In a corner of the garden is a pagoda-style mausoleum. Dinsmoor built it to house his own body and even posed for a double-exposed gag photograph depicting himself looking at his own corpse. When he died, Dinsmoor was embalmed and entombed behind glass, as per his plans. You can still see his smiling but slightly moldy face when you peer into the space.

305 East Second Street, Lucas. The tiny town is about 2 hours north of Wichita.

N 39.057802 W 98.535061

5. Bishop Castle

PUEBLO, COLORADO, U.S.A.

In 1969, at the age of 25, newly married Jim Bishop started constructing a stone cottage for his family. Over the decades, as he kept building, that stone cottage became a castle. Today it is a multilevel marvel with three towers, a grand ballroom, and a fire-breathing metal dragon guarding the main eave. And Bishop still isn’t done.

The castle doesn’t adhere to any building codes. There have never been any blueprints, and Bishop is quick to point out that while his father helped a tiny bit with initial construction efforts, he has done the vast majority of the work himself. (Just to make sure this point is crystal clear, the small section that his dad worked on is painted with the words “Jim started the castle, not his father, Willard.”)

Bishop sees his castle as a symbol of American freedom. Signs surrounding the building tell of the local government’s unsuccessful attempts to regulate his work. “They tried but failed to oppress and control my God-given talent to hand-build this great monument to hard-working poor people,” one reads (in part—it’s a long sign).

Bishop plans to keep building until he is no longer physically able. When visiting, you may see him carrying stones or making an impromptu speech from one of the towers—he is known to unleash his political views on visitors at high volume.

1529 Claremont Avenue, Pueblo. Admission to the castle is free—funding for ongoing construction comes from gift shop sales and donations. The castle is open during daylight hours. From I-25, take exit 74 at Colorado City toward the mountains. It’s 24 miles (39 km) farther along Highway 165.

N 38.240728 W 104.629102

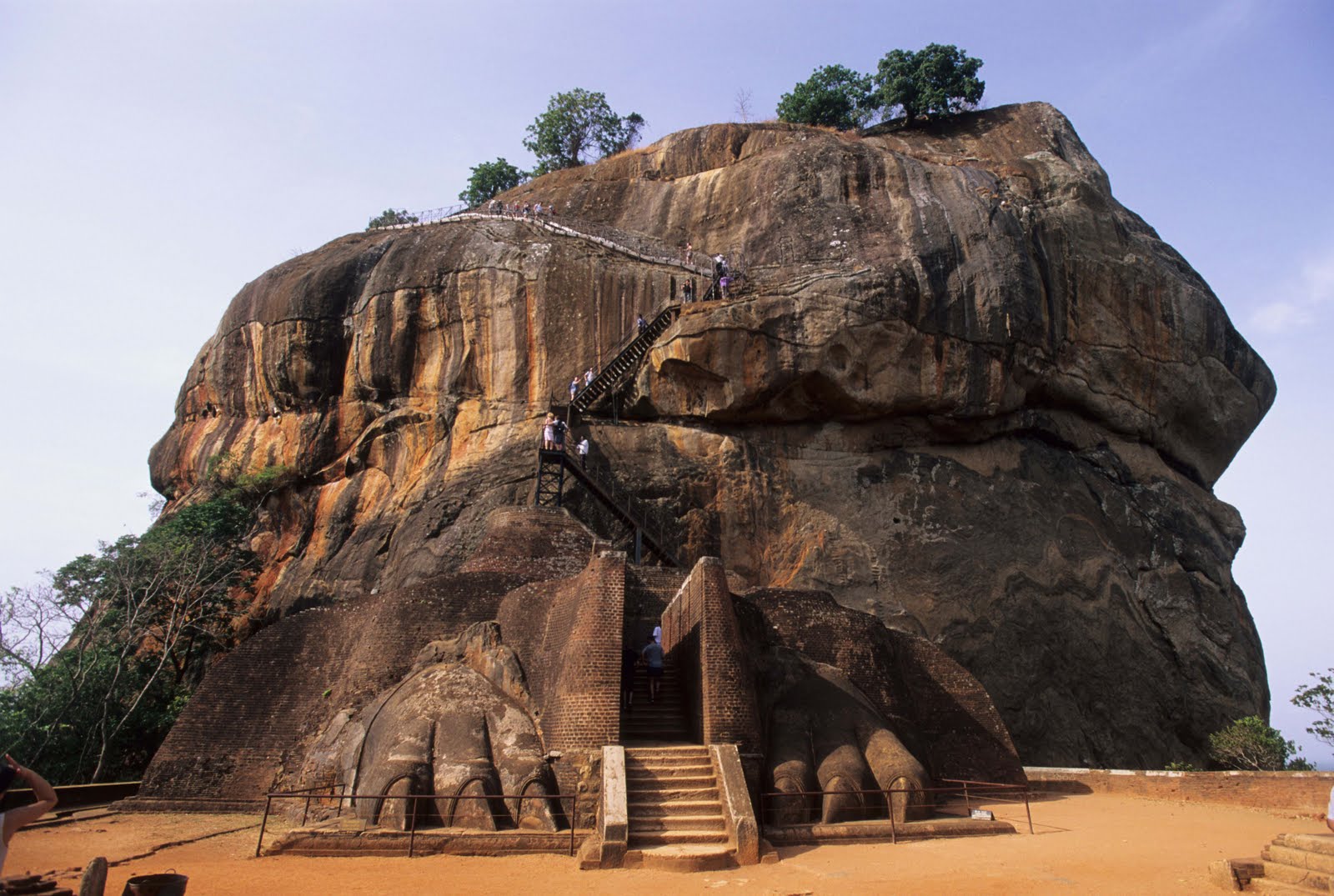

6. Sigiriya

MATALE, CENTRAL PROVINCE, SRI LANKA

When you’ve murdered your father and stolen your brother’s crown, you need to find yourself a safe, vengeance-proof home. For King Kassapa I, who overthrew his father and buried him alive in the wall of an irrigation tank in 477 CE, that place was Sigiriya.

At the center of Sigiriya is the 650-foot-tall (198 m) hardened magma plug of an extinct volcano. Fearing an attack from his usurped brother Moggallana, Kassapa built a palace for himself on top of the rock and surrounded it with ramparts, fortifications, fountains, and gardens. A moat around the rock added an extra layer of protection.

Though Kassapa focused on keeping himself safe, he didn’t skimp on the design details of Sigiriya. The stone stairway leading up the mountain is flanked by two huge lion paws carved into the rock. At the top of the 1,200 steps originally sat a lion’s mouth, which people had to walk through to get to the palace. This explains Sigiriya’s alternate name: Lion Rock.

Kassapa sequestered himself in his hilltop palace for 18 years before his greatest fear came to pass. Moggallana, having recruited an army in India, besieged Sigiriya and overpowered Kassapa’s soldiers. Facing certain defeat, Kassapa turned his sword on himself and, with his death, granted Moggallana the kingship to which he had always been entitled.

For maximum comfort, go early to avoid the heat. From Colombo, get a bus to Dambulla and switch to a Sigiriya bus. The whole journey takes about 4 hours.

N 7.955154 E 80.759803

7. Mudhif Houses

MESOPOTAMIAN MARSHES, IRAQ

For thousands of years, mudhifs—large, arched communal huts made from reeds—have served as social and ceremonial hubs for the Marsh Arabs, or Madan, of southern Iraq. Weddings, dispute resolutions, religious celebrations, and community meetings all traditionally take place within the structures.

To build a mudhif, the Madan assemble 30-foot (9 m) lengths of reeds into bunches and bend them into arches. Rows of these arched columns form the basic structure of the house. Woven reed mats and latticed panels fill the gaps, forming the ceiling and walls. Each tribe’s sheikh collects tributes from families in order to maintain the mudhif.

After the Gulf War in 1991, Saddam Hussein’s regime drained the marshes as an act of revenge against those who had taken refuge there after participating in antigovernment uprisings, transforming the marshes into desert. With their food supply eliminated, about 100,000 Marsh Arabs fled, abandoning their traditional way of life.

With the 2003 defeat of Hussein came the removal of levees and the slow return of water to the marshes. However, droughts, new dams, and upstream irrigation projects have since reduced the levels again. A small number of Madan communities have returned to their old homes and rebuilt their mudhifs, but their ongoing survival in the marshes is far from assured.

The marshes are about 20 miles (32 km) northwest of Basra.

N 31.040000 E 47.025000

8. Painted Village

ZALIPIE, LESSER POLAND, POLAND

Zalipie, a small village east of Kraków, is forever in bloom. The walls of its wooden homes, both interior and exterior, are decorated from floor to ceiling with painted flowers. The village well is covered with carefully colored blossoms. At St. Joseph’s church, a sculpture of Jesus on the cross is surrounded by sprays of flowers painted on the wall. Floral murals curl their way around ovens, roofs, doghouses, and chicken coops.

The Zalipie tradition of painting flowers on every available surface likely began during the late 19th century as a way of dealing with the soot spewed into the air from wood-burning stoves. To hide stubborn spots on the blackened walls, the women of Zalipie took to painting over them, first with a lime whitewash and then with colored flowers. By the time chimneys and modern ovens replaced the soot-spewing stoves, floral murals had become a hallmark of the village.

Zalipie’s flower-painting practice continues to this day. Every spring, the village holds a competition for the best painted cottage.

Zalipie is a 90-minute drive from Kraków.

N 50.238222 E 20.847684

9. Upside-Down House

SZYMBARK, POMERANIA, POLAND

The Center of Education and Promotion of the Region in the village of Szymbark has a bewildering collection of attractions: the world’s largest piano; an exhibit of tobacco snuffboxes; a brewery; and a two-story wooden house that looks to have been uprooted, turned upside-down, and plunked crudely back into place.

The upside-down house, built in 2007, is the work of Daniel Czapiewski, a Polish history enthusiast who manages a factory that makes timber homes. According to Czapiewski, the topsy-turvy house represents the uncertainty and shifting of traditions that accompanied the end of Communist rule in Poland. Its furnishings hammer the metaphor home: A television from the 1970s blares propaganda from the era and the walls are covered in artwork depicting the horrors of poverty, fascism, and famine.

Walking through the inverted rooms, you will likely feel dizzy. The builders who worked on the house felt the same way—they had to take breaks every 3 hours during construction to ward off their disorientation.

12 Szymbarskich Zakładników, Szymbark, a 40-minute drive from Gdańsk.

N 54.218510 E 18.101100

10. Republic of Kugelmugel

VIENNA, AUSTRIA

The Republic of Kugelmugel is one of many “micronations.” These independent states, often established as art projects, social experiments, or simply for personal amusement, are not recognized by international governments.

When creative urges compelled Edwin Lipburger to build a spherical house on his Katzelsdorf farm in 1984, the Austrian artist didn’t think to obtain a building permit. When authorities promptly issued a demolition order, Lipburger responded by declaring his construction, Kugelmugel, an independent nation. The government steered Lipburger toward a jail cell, where he would spend the next ten weeks until the president of Austria pardoned him.

When the strong-willed artist left prison, he found that Kugelmugel had been transported to a Viennese amusement park. The new location, beside a Ferris wheel, was a slap in the face to the earnest Lipburger. In response, he posted a list of his treasonous enemies at the Kugelmugel border, denying entry to all who appeared on it. The names included Mayor Helmut Zilk, who was intent on demolishing the structure.

Kugelmugel is now enclosed in barbed wire, a red-and-white-striped door marking its border with Austria. Its founder no longer lives inside, having been driven into exile.

2 Antifaschismusplatz, Vienna. Get a bus to Venediger Au. Kugelmugel is located in Vienna’s famous Prater park, depicted in Carol Reed’s classic film The Third Man, and is found at the western edge of the park in the shadow of a roller coaster.

N 48.216234 E 16.396221

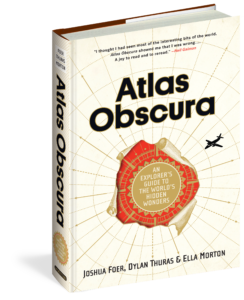

About the Book

About the Book

It’s time to get off the beaten path. Inspiring equal parts wonder and wanderlust, Atlas Obscura celebrates over 700 of the strangest and most curious places in the world.

Created by Joshua Foer, Dylan Thuras and Ella Morton, Atlas Obscura revels in the weird, the unexpected, the overlooked, the hidden and the mysterious. Every page expands our sense of how strange and marvelous the world really is. And with its compelling descriptions, hundreds of photographs, surprising charts, maps for every region of the world, it is a book to enter anywhere, and will be as appealing to the armchair traveler as the die-hard adventurer.

Anyone can be a tourist. Atlas Obscura is for the explorer.

Order Atlas Obscura today!

Amazon » Barnes & Noble » IndieBound » Workman »

No Comments