Manage your stress levels with these calm parenting techniques.

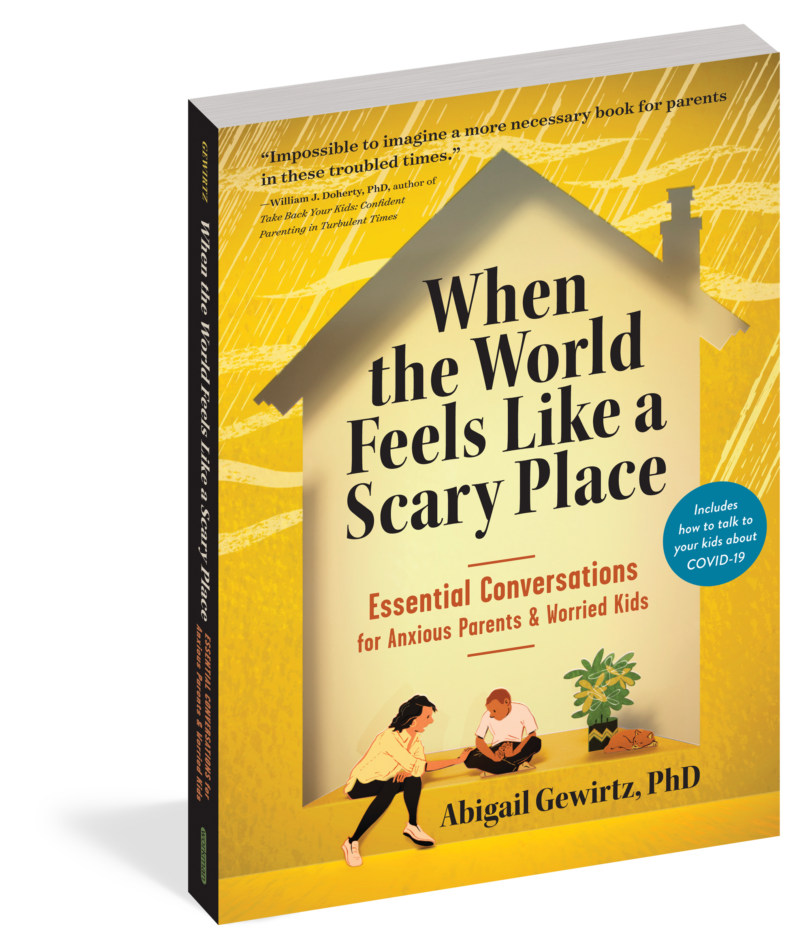

Raising a child can be anxiety-producing enough, without any trouble from the outside world. When current events get to be too much to handle, enter Dr. Abigail Gewirtz and her book,When the World Feels Like a Scary Place. The calm parenting techniques excerpted here will help you control your reactions to bad news, stay calm through difficult situations, and regulate your emotions. Becoming a calmer parent will allow you to help your kids manage their own anxieties, keeping the whole family more emotionally balanced.

Excerpted from When the World Feels Like a Scary Place: Essential Conversations for Anxious Parents and Worried Kids by Dr. Abigail Gewirtz. Copyright © 2020.

UNDERSTANDING HOW YOU PROCESS STRESS

For busy parents, the barrage of bad news coming at you can feel like being inside a video game—and you’re the target. How do we stay calm under fire, true to course and to our values? How do we avoid prematurely pull- ing our “trigger” when we’re agitated and making things worse by hitting the wrong targets? As we’ve seen, anxiety is an important evolutionary signal—it tells us danger is coming. But sometimes our brain tricks us. Sometimes our anxiety arises not from what is actually in front of us, but from what we perceive to be happening—perceptions that are shaped by our personal background and sensitivities. When you keep worries and fear from running away with you, you will be much more effective in help- ing your children deal with scary world events.

As parents, it’s important to figure out what you and your spouse, partner, or co-parent consider stressful. Understanding what makes each of you anxious, and how you differ that way, will help you understand and respond to your children’s anxiety.

EXERCISE: HOW DO YOU RESPOND TO BAD NEWS?

Discuss with your partner how each of you responds to bad news. You need ten or fifteen minutes for this exercise. Pick a time—when your kids are in bed, for instance—when the two of you won’t be disturbed. First, for two to three minutes, each of you should jot down, on your own piece of paper, how you respond to bad news. After that, on another piece of paper, jot down what you each observe in the other’s reaction to bad news. Now, the fun starts!Place your lists side by side. How different or similar are your reactions as you each listed them for yourselves? And how similar or different are your perceptions of each other’s reactions? Compare what you wrote about yourself with what your partner wrote about you. You might be surprised at the similarities, or contrasts, in your approaches.

EXERCISE: THE MIRROR GAME

Researchers generally agree that there are five basic emotions: joy, anger, sadness, disgust, and fear. Those characterize much of what we experience, but you can probably think of more, like embarrassment, excitement, surprise, and shame, to name a few. Physiological responses to stressful events can clue us in to our emotions, but how you are feeling can also, of course, be seen on your face, as any good poker player knows. Extensive research confirms this, and also finds, amazingly, that facial expressions and how we interpret them appear to be fairly universal across culture, race, and nationality.

Try this when you have a few moments alone with a mirror: Select an emotion and express it on your face. Then look in the mirror. Try joy first. What do you notice? Smiling, most likely. But in addition to the upturned mouth and opening of your lips, do you see or feel changes around your eyes? Do you see them narrowing? Are “smile lines” appearing around your mouth? Are your nostrils flaring? Try expressing other emotions and note how the key features of your face change with each.

You can try a variant of this in a game with a friend or partner. Each of you portray an emotion, and then have your partner guess what your facial expression conveys. After you have done this a few times, try something different: Both of you agree on one emotion and each expresses it. Compare your faces as you look at each other. (You can use a mirror or take a photo to make that easier.) Can you find similarities in how you express the same emotion? What’s happening with your faces’ key features? The way you move your eyebrows, mouth, eyes, nose, and forehead reveal a lot. Try this with a few emotions. Focusing on facial and physiological features associated with emotions is a first step to becoming a better reader of your own emotions and others’.

HOW TO STAY CALM

So, now that we can identify emotions, how do we respond to them? We all experience strong emotions, and we can’t just turn them off. What we can do is choose how we respond to them. Responding intentionally rather than reacting impulsively requires putting space between you and your emotions to make room for calm.

Think about a situation that pushes your buttons. For me, a familiar example is severe weather (say, a tornado warning) while I’m driving home from work with the (bad) news playing on the radio. I am stuck in traffic and listening to a(nother) story about the increase in hate crimes. What do I feel? First, dread, running through my veins. My heart beats faster, and I might get a knot in my stomach. Those are my alarm bells.

As I realize what’s happening, my calming strategies kick in. Almost automatically, I’ll take a few deep belly breaths, a five-second inhale followed by a ten-second exhale. I focus on this respiration (not to the exclusion of the road, though, right? I’m driving!). Then I sort through my options. One source of my stress is the news, so off goes the radio. I’ll opt for silence or mellow music instead. With that fixed, I’ll take steps to ground myself, to immerse myself in my surroundings and what I’m doing right now, using as many senses as I can: I’ll feel the press of my palms on the steering wheel, listen to the pat-pat of rain on the car windows, focus on the colors of the cars around me, their shiny wet surfaces, the dull light of the gray skies. These sensations usually help bring me back into the present. Focusing on the here and now frees me from getting stuck in anxious thoughts that might otherwise spiral, and also makes me a safer driver. Once I am more present, I am less likely to react impulsively in ways I might regret, like banging the steering wheel or driving too fast.

Here are some strategies that have worked for me and many others:

• Take ten deep breaths. Breathe slowly in through your nose. Fill your lungs and let your belly rise. Breathe out even more slowly. Breathe out through your mouth as if you are filling a balloon. Feel your belly fall as the air comes out of it. Make your exhale longer than your inhale; make it last ten seconds, if you can. (See the resource section for audio links to help guide you.) Deep breathing is a strategy that’s available to you anywhere, anytime. In fact, it directly counteracts a harmful tendency toward unusually shallow breathing when bad things happen. When we panic, our breath starts to come from the chest, rather than the belly or diaphragm. Shallow breaths deprive us of oxygen we need, inducing a shortness of breath that makes us even more anxious. In the extreme, this is what brings on panic attacks: Short breaths increase our agitation because we feel like we are struggling for air. Reaching deep into our bellies for air increases oxygen exchange, by contrast, slowing heart rates, decreasing blood pressure, and stanching the impression that we are, quite literally, suffocating.

• Take a content break. Switch off the news. Put down the computer or phone. Set aside the newspaper.

• Walk away. Just leaving the room can help, but a short walk outside can work wonders. If you can’t walk away, ground yourself where you are. Put your senses to work: Feel your feet in your shoes, your shoes on the floor, the smells and sounds around you. Focus on these physical reminders of where you are, and let them draw your attention back to your physical presence and away from the turmoil in your mind.

• Use humor to lighten the situation and defuse tension.

• Ask questions. This lets you gather information as well as buy time—time to distance yourself from intense negative feelings, and time to plan or strategize.

• Listen. Listen to whoever you’re with, especially if it’s a child or if you’re in a conflict situation. (We’ll learn more about intentional listening in chapter five.)

• Distract yourself. If nothing else works, consider listening to music, picking up a magazine or book, watching TV, or squeezing a stress ball.

Once you’ve had a chance to list or think through strategies that work for you, turn to your partner and find out what works for him or her. Compare your lists. How different are they? Are you surprised, or did you already know what calms them down?

All of these methods can help you interrupt negative reactions to intense emotions in the immediate term. Over the long term, there’s even more you can do to train your mind to be less reactive and more calm. Activities like mindfulness meditation, prayer, yoga, and Tai Chi can help you to buffer intense negative reactions. They also can feel good, serving as a form of healthy “me time” and an outlet for blowing off the steam of day-to-day living. Fortunately, they can be cheap or even free. Meditation and yoga audio and video on the internet, and numerous mindfulness apps offer exercises, lasting from a few seconds to an hour or longer, that you can customize with ambient sounds, music, gongs, or silence. Emotion regulation tools are like exercise: The more you practice, the easier it comes, and the more skilled you get.

More About When the World Feels Like a Scary Place:

“A terrific book for parents who want to know how to talk about difficult, emotional issues with children.”––Nancy Eisenberg, Regents’ Professor of Psychology, Arizona State University

“A terrific book for parents who want to know how to talk about difficult, emotional issues with children.”––Nancy Eisenberg, Regents’ Professor of Psychology, Arizona State University

“Remarkable… Compelling advice illustrated with memorable case examples.”––Ann S. Masten, PhD, Irving B. Harris Professor of Child Development, University of Minnesota

In a lifesaving guide for parents, Dr. Abigail Gewirtz shows how to use the most basic tool at your disposal––conversation––to give children real help in dealing with the worries, stress, and other negative emotions caused by problems in the world, from active shooter drills to climate change.

But it’s not just how to talk to your kids, it’s also what to say: The heart of When the World Feels Like a Scary Place is a series of conversation scripts––with actual dialogue, talking points, prompts, and insightful asides––that are each age-appropriate and centered around different issues. Along the way are tips about staying calm in an anxious world; the way children react to stress, and how parents can read the signs; and how parents can make sure that their own anxiety doesn’t color the conversation. Talking and listening are essential for nurturing resilient, confident, and compassionate children. And conversation will help you manage your anxieties too, offering a path of wholeness and security for everyone in the family.

No Comments