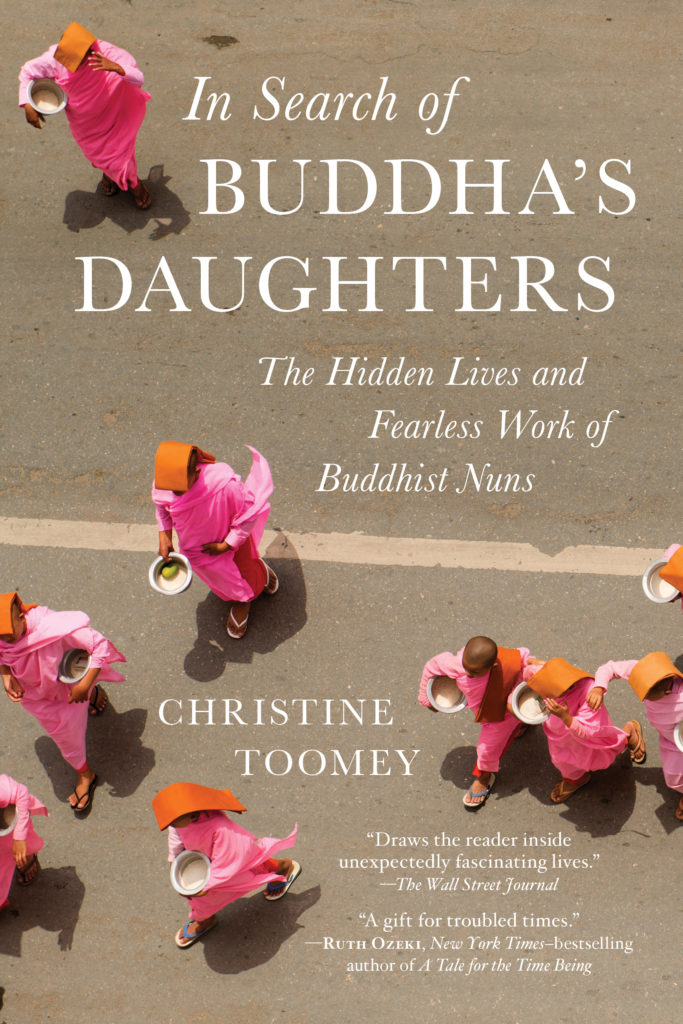

Welcome to our new #FridayReads feature on the blog. Every week, we’ll be excerpting a chapter of one of our favorite books to kick off your weekend. This week, it’s award-winning journalist Christine Toomey’s In Search of Buddha’s Daughters, a vividly reported 60,000-mile odyssey in search of Buddhist nuns—hailed as “inspiring and necessary” (Kirkus).

Hooked? You can buy it here.

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

At the Druk Gawa Khilwa nunnery, nestled in mountains an hour’s drive from Kathmandu, each day begins at 3 a.m. with the sound of a bell. Dawn will not seep across the highest Himalayan peaks for several more hours. As the young nuns stir from sleep, only a dim light filters through the dormitory windows from lit pathways beyond.

No words are spoken and no glances exchanged as the young women slip from their beds and wrap their slender frames in burgundy and saffron robes. First, an underskirt and shirt without sleeves, worn even on the coldest of days. Over this, a wide lower robe is folded and tucked at the waist. Finally, a long shawl, a zen, is tossed around the shoulders to keep out the chill. After smoothing out sheets and blankets, each woman steps up onto the firm mattress of her bed and sits cross-legged facing the wall against which her pillow rests. Each then turns within, entering the realm of meditation.

While most of the sisters spend the next two hours treading their own inner path, repeating secret mantras and recitations given to them individually by the head of the Buddhist order to which they belong, alternate groups of nuns take it in turns to follow a very different form of practice. Instead of monastic robes, they lift a different set of clothes from the storage boxes under their beds: loose brown trousers and long-sleeved martial-arts jackets cinched at the waist with a cloth sash. Tying the laces of white canvas shoes, they pass quietly from their dormitories into the night air.

It is mid-October when I join them and together we snake up a stairway that leads from their residential complex, along a steep incline bordered on either side by scented flowers and shrubs. The stairs lead to a large hall in front of which stands a giant gilded statue of the Buddha. If the weather is too cold, the nuns take up formation inside the hall. But today, as it is warm enough to practice outside, I follow the women as they climb three further flights of stairs onto the roof and space themselves out with a few low whispers. As their instructor brings the group to order they draw their feet together, pull two clenched fists back towards their waists and stand waiting.

At the opening command they raise their arms to shoulder height, thrust their right fist into their left palm and spring into such sharp action that it seems a temporary affront to the calm devotions of those meditating below. In the background, the only sound is a gentle symphony of cicadas, but high on the nunnery roof the peace is now pierced by the shouted instructions in the practice of kung fu. With each position counted out, the nuns move through a series of steps that ow from graceful hand gestures through fierce air punches and swinging chops to soaring kicks and acts of fighting.

Most of the exercises are carried out with each nun going through the motions individually, either with bare hands or with the long fighting sticks known as bo staffs. The most startlingly beautiful are performed with blood-red fans swirled above the head and around the nuns’ waists. At times the fans are spun open, at others flipped closed, the effect more dance than martial art. Other exercises involve two nuns sparring, circling each other with clenched fists, thrusting, shoving, grabbing the other’s neck in the crook of their arms and pushing their opponent to the ground. Some of the moves are conducted with the fighting sticks held in both hands and used as both shield and weapon. As each series of maneuvers comes to an end, the nuns again draw their fist into their palm then push their open hands slowly down by their sides. It is only this subtle closing movement that returns to the women the gentle demeanor of their monastic calling.

What I am witnessing in this striking pre-dawn display is more than 1,000 years of tradition being turned on its head.

For more than a millennium this practice of kung fu was reserved only for monks, its roots lying far to the north in the legendary Chinese monastery of Shaolin. It was here in the fifth century that kung fu was said to have originated, after Bodhidarma, an Indian prince turned Buddhist monk, set out to take the teachings of the Buddha to China. On finding temples there vulnerable to a attack by thieves, and many of the monks struggling with the rigors of monastic life, the monk devised a system of fitness and defense that drew heavily on the ancient traditions of Indian yoga. Like yoga, Shaolin kung fu developed from an observation of the way animals move. Over the centuries the Shaolin monks incorporated many different animal postures into their practice until eventually the mastery of many of these styles developed into a form represented by a dragon. Unlike the re-breathing dragon of western mythology, the Chinese dragon is a powerful spiritual creature.

It is telling, then, that the nuns of Gawa Khilwa belong to the Drukpa order of Tibetan Buddhism, druk being the Tibetan word for both ‘dragon’ and ‘thunder’.

As the first blush of sunlight bleeds over the horizon, the nuns draw their morning kung-fu practice to a close. A deep rumble of drums can be heard in the distance and high on the roof of the nunnery’s main temple I see the silhouettes of two figures blowing hard into gold-and-jewel-encrusted conch shells. is piercing bugle call is the Buddhist call to prayer. It is barely 5 a.m. and two hours of elaborate ritual and worship in the temple will follow before the nuns and I sit down to breakfast.

The ferocity of these morning exercises at Gawa Khilwa seems the antithesis of spiritual endeavor. But this practice I am privileged to have observed not only builds the women’s physical and mental strength, it also instils in them a growing sense of confidence. is is an entirely new experience for Buddhist nuns, who, through the centuries, have often been neglected and overlooked.

About the Book

About the Book

A 60,000-mile odyssey in search of Buddhist nuns—hailed as “inspiring and necessary” (Kirkus), “ambitious” (Tricycle), and “compelling” (Financial Times)

They come to the monastic Buddhist life from every faith and career: a policewoman, a princess, a Bollywood star, a violinist. Out of the public eye, despite hardship and even persecution, they vow to seek enlightenment in a world full of noise.

Who are these women? What motivates them, and what stands in their way? Award-winning journalist Christine Toomey investigates. From Nepal to California, she encounters unforgettable nuns who reveal the blessings—and perils—of carrying a 2,500-year tradition into the twenty-first century. Often denied equal status with monks, they are nonetheless devoted—to their faith, and to change.

No Comments