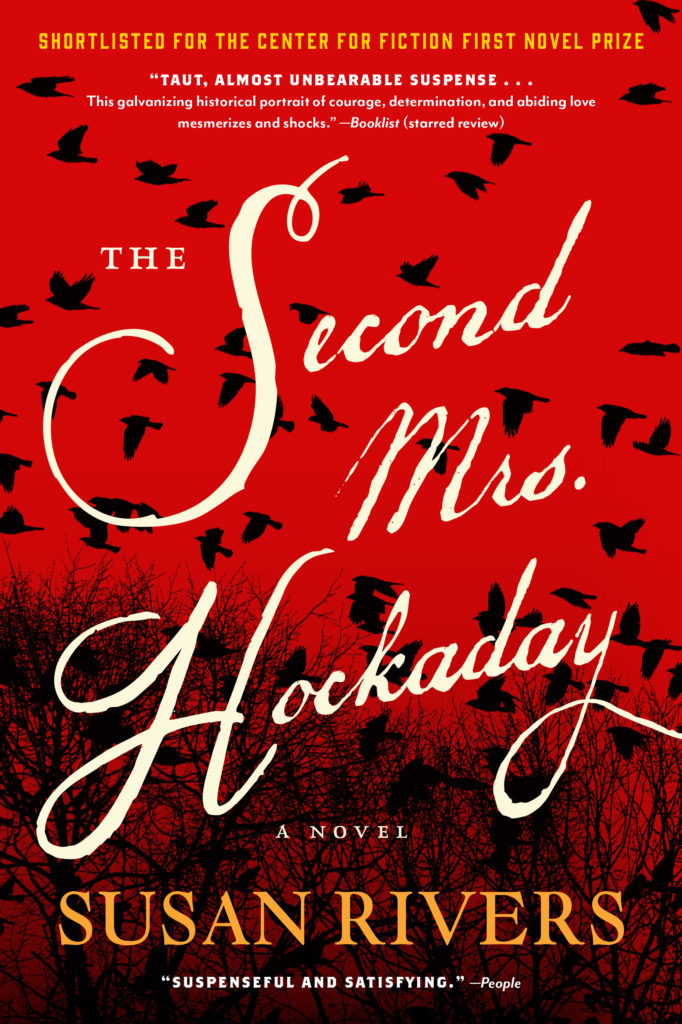

Welcome to our #FridayReads feature on the blog, where we’ll be excerpting a chapter of one of our favorite books to start your weekend. This week, it’s Susan Rivers’ The Second Mrs. Hockaday, which was shortlisted for the Center for Fiction First Novel Prize. A love story, a story of racial divide, and a story of the South as it fell in the war, the novel reveals how that generation—and the next—began to see their world anew.

Scroll down for an excerpt.

The Second Mrs. Hockaday

3982 Glenn Springs Road, Glenn Springs, South Carolina

September 29, 1865

Dear Millie,

Dr. Gordon knew my father when they were students at South Carolina College. He did not realize whose daughter I was when he performed the examination of my baby’s remains; that is how I am assured of his objectivity, a rare attribute in local people of my acquaintance. While the extent of decomposition prevented a conclusive cause of death, the doctor reports that the child did not suffer trauma, and while drowning or suffocation cannot be entirely ruled out, he concludes that he most likely died of exposure. It was not the doctor’s opinion that I exposed the baby intentionally–that accusation comes from the magistrate. The doctor asked to speak to me, however, after examining the remains, and that is when we discovered our connection. I learned what an empathetic man he is (also rare). When Dr. Gordon’s son was fighting at Second Manassas, his young wife, unbeknownst to her husband, was dying along with her breech infant in Leesville. The doctor was in Richmond on work for the government at the time, or would have been at his daughter-in-law’s side. In the aftermath, he worried that his son had developed a very dark outlook, believing there was little purpose in his soldiering when it had cost him the souls dearest to him. Dr. Gordon tells me that he has worked hard to persuade his son that there is a time for war, and when war has been put behind us at last, people will find a way to mend their lives and go back to the full enjoyment of life. That is our natural inclination, he says, and I understand that he means to be encouraging where the major and I are concerned. The soldiers who have lost much will be dissatisfied and angry for a time, he tells me, and may, in their confusion, lash out at the people fondest of them. This will be truest for those who served most loyally, yet for all their courage and purity of purpose found themselves in the ranks of the vanquished, trudging home with little more than the shirts on their backs. It will be more difficult for these warriors, he counsels. They have buried so many comrades, only to find that deliverance will elude them unless they can also bury their shame.

As for my reunion with the major, the moment was unlike anything I expected, despite the fact that I had rehearsed all plausible scenarios a hundred times in the months before he finally returned. Such a gulf stood between us, such a tumult of unexpressed emotions and thoughts, that we were rendered nearly mute by the anomalous quality of our encounter. I do remember that he asked me questions which I tried to answer honestly, if I could do so without implicating others. I took him to the spot beneath the swamp-rose where the child was buried. He wept (I had never seen a man do such), but whether it was for the child, for my sake, or for the wrong done him, I could not determine. One thing was fully evident: he is not the same man. Nor am I the same woman. Our experiences have marked us. Shaped us. And none of those experiences are shared. His hand looks strange with the middle fingers missing; more significantly, Millie, Gryffth has lost that raptor-sight that characterized his intelligence so splendidly. His dark eyes are flat—no longer interpreting, discriminating, divining. Maybe he had to sacrifice that gift in order to survive. Or perhaps it was torn from him in the violent battery of war. But now he only sees what is set before him. That is all he wants to see. Or needs to.

In marveling at how transformed he is, I strive to keep in mind that I am changed quite as totally as the major. It is challenging to remember the child who stood up before Rev. Poteat two years ago with a handful of spring flowers and a joyous heart, who trusted her fate to the good luck she had been born with and to a man blown into her path by the prevailing winds. Cousin, you asked me what transpired when I spoke with Major Hockaday on the morning of our wedding, after I told my father I would see my suitor before making a final decision. I shall tell you, but I doubt it will provide the unifying explanation your mind seeks.

I knocked before entering Father’s study, although it felt strange when I knew Father was not inside. I heard Gryffth speak and opened the door to find him standing at the window Q. V. favored, the Richmond papers lying untouched upon the desk.

Miss Fincher! he exclaimed, as if he had not expected to lay eyes on me again.

Major . . . I began, but faltered, not knowing how to proceed.

He was thinner than I remembered from the day before. More careworn. It reminded me that he had lost his wife less than three months earlier and had nearly buried his baby son. In addition, he had been far from home, fighting a war. His face was unshaven and his uniform, I noticed, looked shabby in the morning light, as if he had tumbled it with a bag of rocks before donning it to call upon my father and stepmother. He was as strange to me as a manatee, dear Cousin. Or an Indian chief. And yet I recognized that he was fully at ease with the man who stood gazing at me from across the carpet: he was open, authentic, concealing nothing—not even the diminution of strength and spirits he was feeling, considering his troubles. The scant value he placed on appearances was also evident in the way he looked at me. Since my sixteenth birthday I have been conscious of how certain men, especially those who lack good breeding, study me as if I were a confection being wheeled past on a cart. A gleam of appetite sparks in their eyes as they take in my face; their gaze moves to the rest of me and evaluates the substantive components along with the decorative ones, weighs the whole, and then returns to my face with the eyes now veiled by a scrim of pretense (easily penetrated, if they only knew!) that attempts to feign mild admiration not yet linked to acquisition. The major’s black eyes, however, did not rove. They fixed on my face and remained there, as if plumbing a body of clear water for its depths. Because their lucent focus was fully unfiltered, I was able to detect the slightest quality of apprehension fluttering there: not as if he feared to be revealed to me, but as if he doubted his right to engage my commitment on the same spartan terms of self-disclosure.

I cannot explain the impossible sensation that stole over me of knowing this man in the deepest recesses of his spirit, of knowing him as intimately as if I were him. Or him me. The thought made me blush, but I did not question it, any more than I had questioned the honeybee in my closed fist. Perhaps he read this in the smile I ventured to offer, for he stepped inside the wreath of vines I occupied on the carpet and ducked his head to look into my face.

I am not wealthy, he said at last. Or handsome. And I’m a long way from “refined.” In other words, I am not the husband you deserve, Miss Fincher. But this is what I know: to wake up beside the person you cherish and who cherishes you in return . . . there is no better refuge from the world than that. Whatever hardships may come. And they do come. They will.

He took a step closer. My heart was thumping so hard I had to sit down or collapse from lightheadedness. I sat. He hesitated, looking about for a straight chair to pull up beside me, but the only one in the room stood behind Father’s desk, and I could see he did not want to take that liberty. After a moment he improvised, resting his hip gingerly on the edge of the desk. His skin, as he leaned close to me, smelled like a sawn plank of cedar.

Despite what I feel, he said quietly—and what I feel is genuine, resolute—I will not presume to lay claim to such a tender and unsullied heart as yours, fair girl, unless you tell me I am correct that in the short time we have been acquainted, you have experienced affectionate regard for me . . .? You “recognize” me, in some way?

He sat waiting for my answer, but not pressing for it. Because I was too flustered to look him in the face I studied his left hand where it lay on the edge of the walnut desk. His big knuckles gripped the carved edge, the brown skin weathered and crosshatched by scars acquired over the two years he had lived on battlefields and traveled rough country. Without knowing what I was doing I lifted my own hand and placed it flat beside his on the desk, spreading my fingers in a vain attempt to increase the span. His eyes dropped from my face to our hands and we compared them together: the dark and the pale. The rough and the soft. The tested and the untested. Husband and wife. We looked at each other then, and smiled. That’s how it was decided. As simply as that.

I believed him, you understand. About marriage being a refuge. I want to believe him still. But lifetimes have passed since I woke up beside my husband. And I can no longer claim to be cherished.

Your loving cousin,

Dia

Hooked? You can buy the book here.

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

No Comments