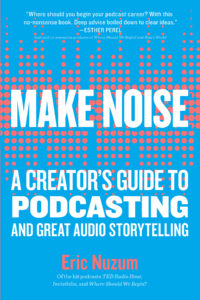

It’s the fastest growing media platform in the world. Here’s how to start your own podcast.

Have you been wondering how to start a podcast? MAKE NOISE: A Creator’s Guide to Podcasting and Great Audio Storytelling imparts all the wisdom, advice, practical information, and big-picture thinking that any individual or business needs to make a successful podcast.

Written by Eric Nuzum, a veteran of NPR and Audible who’s had a hand in creating and launching more than 130 podcasts, including TED Radio Hour, Invisibilia, and Where Should We Begin? with Esther Perel, MAKE NOISE offers an analysis of the medium, examining its promise, its drawbacks, what it offers to creators, and how to bring it all together.

Whether you’re a curious novice looking to start something new or someone interested in using podcasting to forge connections and share ideas, this is your go-to guide for recording, editing, hosting, and submitting your podcast. Nuzum dives deep into how to develop character, story, and voice; how to conduct an effective interview; and how to be mindful of the limitations of audio and sound quality, all so you can turn your good idea into a great idea. Start reading, so you can start recording.

* * * *

Hi. I’m glad you are here.

I’ve been told to set my expectations low for this introduction, that “no one reads an introduction.” Well, thank you for showing that assumptions are dangerous things and rarely work out the way people think. (That’s a theme we’ll touch on a lot in our time together.)

Let’s start off with a truth: I’ve never heard a perfect podcast. Ever. I’ve also never heard a podcast that didn’t have lots of room for improvement (including my own, by the way).

Even the best work I’ve ever done never felt fully finished to me. I felt there was always something I could do to make it better. That’s one reason that I rarely go back and listen back to things I’ve produced in the past—all I can hear are the things I should have caught, tweaked, improved, or fixed. The French poet Paul Valéry once said, “A poem is never finished, it is only abandoned.” The same can be said for a podcast episode.

A good audio creator balances confidence and humility. They have a clear and confident idea of what they want to create and how to create it, yet they also realize that the podcast will only be as good as they make it. The true limits of its potential are the limits of their own skill.

I’ve also heard it said that “overconfidence is the enemy of good thinking,” and I think that applies to audio production as well. Overconfidence can prevent creators from seeing the opportunities in front of them to make their work stronger and resonate with more people.

That’s why this book exists. To embrace that truth and the realities that come with it. As a creator, I believe in boundaries. Not as in narrow thinking, but that the best creativity comes from working around purposeful restrictions. Focus.

Whether you are new to podcasting or have lots of experience, finding a balance—between confidence and humility, between being clear and focused, while remaining open, and understanding that there is always an opportunity to improve—is the nucleus of this book.

I want to review three things before we get into Chapter 1 that I think will make your time with me more useful and productive: a bit about me, a bit about you, and a bit about the thing that connects us— an interest in podcasting.

A BIT ABOUT ME

There are three dates that are important to understanding what led me to write this book and, thus, you to be reading it.

The first: July 25, 2008. It was a day that changed my life, though I had no idea of that at the time. I stood in the control room at National Public Radio’s New York bureau watching a group of colleagues through a large glass window; they had their arms around one another, many in tears, some crying. It was the last broadcast of a show that NPR had debuted just ten months earlier called The Bryant Park Project. Before the show had even hit its first birthday, it was being shut down, staff laid off, and all the money, time, and energy that went into creating it was written off as a huge and expensive mistake.

The idea for The Bryant Park Project had come almost two years earlier as part of NPR’s agreement to provide two channels for satellite broadcaster Sirius (now known as SiriusXM Radio). Sirius wanted something new and original from NPR, so we dreamed up Bryant Park—an alternative morning news and chat program to NPR’s flagship program Morning Edition, which would be offered exclusively on Sirius satellite radio.

By the time it launched on October 1, 2007, new ideas and initiatives were piled on top of the original concept: In addition to being a morning program, The BPP was also a podcast, and a blog, and a video series, and was also broadcast on a few terrestrial NPR stations, plus a few other things as well. That was the hidden lesson of The Bryant Park Project. It became so many things that it actually was nothing at all. The project had bloated to the point that no one, including those who initially created it, could really define it anymore.

After telling the staff and publicly throwing in the towel, we picked the date for the last show: July 25, 2008. On that day, I went up to the NPR New York bureau to be there for the last show. During the final segment, host Alison Stewart brought Senior Supervising Producer Matt Martinez and the entire staff into the studio. They all talked about favorite moments, acknowledged one another’s talents and dedication to the project, then said goodbye to the audience they had spent the last ten months building. I watched all this pain and remember saying to myself, “I will never let this happen again.”

Even then I knew I could not prevent failure. But there were so many red flags on this journey—so many signs that things weren’t right. There were so many questions that could have been asked and answered earlier. If that work had been done, it wouldn’t have guaranteed a different outcome, but it certainly could have provided a stronger chance for survival. Having a clear definition of what the show was (and what it wasn’t) wouldn’t have prevented a once-in-a-generation economic event, but it certainly could have prevented a dozen talented young people in tears wondering why they had poured themselves into a project for a year, yet were told they had failed, though no one could clearly express how or why. You couldn’t even have a real conversation about whether The Bryant Park Project was “good” or not, because no one could really agree what it was.

There has to be a better way to do this, I remember thinking. There has to be a way to mitigate a lot of this lack of clarity and these abundant unknowns. I will never let this happen again.

The second important date happened six and a half years later: January 10, 2015. On that day I was riding the Metro through downtown Washington, DC. The train was pretty busy for a Saturday, but it was still quiet enough that I could hear a conversation across from me. One couple was telling another couple about a story they had just heard on a new podcast, called Invisibilia. It was the story of Martin Pistorius, a man who had been trapped inside his paralyzed body for twelve years, unable to communicate. It was the lead story in the first episode, which had only debuted the day before.

Right then I knew that my work, as well as podcasting in general, had really taken a new and uncharted turn. And an exciting one, too. I was the executive producer for Invisibilia’s first season. It was a show I had just spent the better part of a year working on, and I was experiencing a holy grail/white whale/unicorn moment: hearing random people in public professing their love for something I helped make happen. The moment went by so quickly. I immediately texted my wife and told her about it. “You sure?” she texted back. “Perhaps they were just talking about something that sounded similar. Trains are noisy, you could have gotten confused.” I didn’t blame her for being skeptical; it was a really weird thing to have happened. The show was less than two days old. So, I reluctantly agreed with her. It couldn’t have been, I thought. Then, the very next day, my wife and I were out to lunch and, mid-meal, I realized that the woman at the very next table was sharing something familiar with her four lunch mates.

“I heard the most amazing story,” she said. “On this new podcast . . . I think it’s called Invisibilia or something like that.” She told the exact same story about Martin and his paralysis.

I looked at my wife. She’d heard it too. Neither of us could believe it. Once, maybe, but twice? Within twenty-four hours?

A lot of people loved Invisibilia. That first season was downloaded tens of millions times in the weeks following those two encounters. And the reason this all made me so happy was because Invisibilia’s success wasn’t really an accident.

My role in Invisibilia came about when one of its cofounders, Alix Spiegel, shared an early version of one of the episodes with me and asked if I could help her and her cohost, Lulu Miller, make this into a show. At the time, I loved the stories they were working on, and was really honored that they trusted me enough to help make their passion a reality. But a lot of the lessons of the past were very fresh in my mind.

The decisions we put into birthing Invisibilia were a culmination of the better part of a decade I’d spent creating new radio shows and podcasts since the end of The Bryant Park Project. Testing. Learning. Deconstructing. Trying again. Never letting “that” happen again. I’d spent a lot of time thinking about podcasts, why they work, why they didn’t, and what their appeal is. I’d also spent a lot of time making podcasts. I tried to infuse all I’d learned into this new show I’d helped bring into the world. I’ve heard it said that luck is preparation meeting opportunity. That was certainly the case here.

Not everything can (or should) be an Invisibilia, but many podcasts, or ideas for potential podcasts, or really all forms of storytelling, could be much better than they are.

That’s why I wrote this book. I wrote it to make your work better.

Before you praise me for my altruism, know that I wrote this because I love to listen. So by helping you, I’m making sure there are more good things for me to listen to. But the reason I spent two years of my life writing this book is that I believe that in serving you, you will learn to serve others—: listeners.

That brings me to the third date that is important to understanding this book and me, which happened years before either of the other two: June 1, 1998. It was the day I started work as the program director at WKSU, a small NPR station in Kent, Ohio. I was thirty-one years old and in charge of the entire on-air staff, programming, and sound of the station. The twist is that WKSU was the radio station where I got my first job in radio when I was nineteen. So not only was I now the boss, but everyone who worked for me was older than me (some twice my age), far more experienced than me, and a significant number of them had known me since I was a teenager. This was all far from ideal for a new boss.

How was I going to be the leader of a group that had taught me a sizable amount of what I knew? How could I be the authority in a room of authorities? In a momentary instance of smart thinking, I decided that the only way I could lead this station was by devoting myself to serving its staff. Together we would design an ambitious vision of what was possible and I would help them attain it. I would lead by serving. Their success was my success. It got us away from bosses and reporting lines and generational differences, and helped us all unify around clear and shared ideas and goals. I made sure I was on the front line of our quests, and made sure that I was the one working as hard or harder than anyone else to reach them.

That’s both a philosophy and a way of leading that I have honed since then and still follow to this day: lead by serving. In my mind, creators serve audiences, and I serve creators. That is what I do. It’s been the basis of my entire career. That perspective has led me to many new ways to think and create, which form the foundation of this book.

I don’t have all the answers and I certainly can’t make anything a hit. In fact, sometimes it feels like quite the opposite. In my career, I’ve had a hand in birthing more than 130 podcasts, radio programs, streaming channels, and other audio projects. I’ve made every conceivable mistake along the way and been responsible for some colossal screw-ups. But over the years I’ve come up with a quiver full of exercises, questions, processes, and ways to approach problems that have helped me avoid the most common mistakes I see and hear in my work and the work of others. They have also led me to a string of successes as well. Given the explosion in both podcast creation and listening in the past few years, it seems like the perfect time to share all of them, as well as the principles and ideas behind them. So, if you are a really impatient person, the rest of this book boils down to two things:

• Know what you’re making.

• Stick to it.

And, as I’m sure you can guess, neither is as easy as it seems.

More About Make Noise: A Creator’s Guide To Podcasting and Great Audio Storytelling

Podcasting is the fastest-growing media platform in the world, with currently 650,000 podcasts out there, in 100 languages, and offering over 20 million episodes. And we’re only at the beginning. More and more podcasts appear every day, and more and more entrepreneurs, businesses, individuals, and distributors, like Spotify, are getting into this world. One person so many people turn to to help launch their podcasts is Eric Nuzum, a veteran of NPR and Audible who’s had a hand in creating and launching over 130 podcasts, including some of the most successful out there like TED Radio Hour, Invisibilia, Where Should We Begin? with Esther Perel, The Butterfly Effect, and West Cork. And the reason is that Nuzum understands the essentials of what makes a podcast work, and knows how to help creators shepherd their vision from rough idea to finished product.

Podcasting is the fastest-growing media platform in the world, with currently 650,000 podcasts out there, in 100 languages, and offering over 20 million episodes. And we’re only at the beginning. More and more podcasts appear every day, and more and more entrepreneurs, businesses, individuals, and distributors, like Spotify, are getting into this world. One person so many people turn to to help launch their podcasts is Eric Nuzum, a veteran of NPR and Audible who’s had a hand in creating and launching over 130 podcasts, including some of the most successful out there like TED Radio Hour, Invisibilia, Where Should We Begin? with Esther Perel, The Butterfly Effect, and West Cork. And the reason is that Nuzum understands the essentials of what makes a podcast work, and knows how to help creators shepherd their vision from rough idea to finished product.

Make Noise brings all the wisdom, advice, practical information, and big-picture thinking that any individual or business needs to make a successful podcast.

Buy the Book

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

No Comments