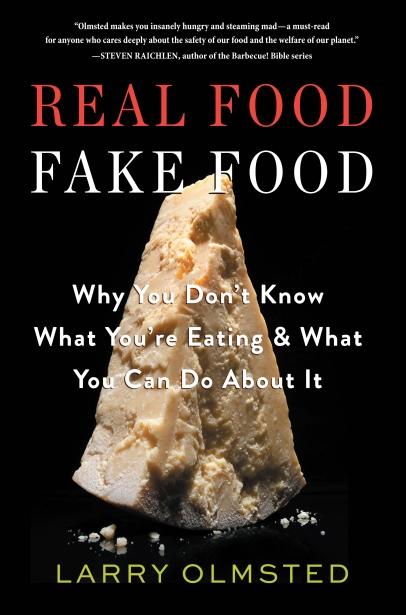

Chapter 2: What is Fake Food?, Excerpted from Larry Olmsted’s New York Times bestseller Real Food/Fake Food.

None of us likes being swindled, particularly when all we were trying to do was buy something nice to eat . . . Being cheated over food is one of the universal human experiences.

—BEE WILSON, Swindled

Before we go any further down this road, let’s get some paperwork out of the way. I’m planning to use the terms Real Food and Fake Food quite a bit in these pages, and since different people might interpret them differently, it is important to clarify what exactly I mean.

Real Food is straightforward—it is what it says it is. Living in New England, one of my favorite examples is the whole Maine lobster, more accurately the North Atlantic lobster, because they are exactly the same in Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Connecticut, Rhode Island, and Canada. We all know what these creatures look like, and when served whole they cannot be faked, even by relatives like the spiny Caribbean or Mediterranean lobsters. Maine lobsters are always wild caught and never farmed or artificially raised; as a result, you don’t have worry about whether they were “natural,” “free range,” or “pasture raised.” They aren’t fattened with hormones and antibiotics that are hidden from consumers, and they aren’t crossbred with cheaper shellfish to make hybrids. They are simply lobsters.

But most important, they are delicious, and while some lobsters taste slightly better than others, and fans passionately argue the merits of steaming versus boiling and soft shell versus hard shell (same lobster, different time of year), it is virtually impossible to get a bad whole Maine lobster—I’ve never had one. You crack it open, you pull out big chunks of rich, flavorful, moist meat, dip them in melted butter to make them even richer, and you have one of the world’s great meals. Just writing these words makes me want one. Whether you go the lazy man’s route and pay someone to break it for you in a white tablecloth restaurant, or roll up your sleeves at a beachside picnic table and dig in, it tastes equally good, and no matter which you choose, you will end up deeply satisfied and licking your lips.

Most Real Food is not so obvious. If I put a glass of actual red Burgundy on the table next to a glass of fake California “Burgundy,” you’d be hard pressed to tell by looking which one was real. But if you tasted them, you could discern the imitator right away, even with little wine knowledge, because it will not come remotely close to replicating the quality of the real thing.

When you already know it is genuine, because you see the bottle of red French Burgundy, you have a different kind of Real Food example: not only is it what it says it is, but what it says is a very specific promise. If the Burgundy could talk, this is what it might say: “My name means something. It means I am made from nothing but 100 percent pinot noir, with no exceptions. This is because the place I come from is world famous for the quality of its pinot noir grapes, where vineyards have been tended for more than two thousand years. Further, my country’s government assesses and rates the qualities of individual vineyards within my region, and by law I can only be made from grapes from the best ones.”

Conversely, the California “Burgundy” might say, “Burgundy is a famous high-quality wine from Burgundy, which is in France, and by putting its name on my label I’m hoping to trick you into confusing me with that wine. Because I can’t compete on quality, I’m not even going to bother trying to imitate real Burgundy. What is pinot noir anyway? I’m a blend made of whatever grapes were selling most cheaply this year, and next year when they make another huge batch of me in big tanks, I’ll have a different recipe.”

Not all Fake Food is equally fake, and throughout this discussion you’ll see that there are three main ways in which food is faked.

ILLEGAL COUNTERFEITS

This is perhaps the most understandable scam—when I say fake Nike or Gucci, you know exactly what I mean. This is the case of someone actively counterfeiting, making an unofficial or unlicensed copy of an existing individual product, usually a high-value brand. A good example happened in 2014 when Italian authorities seized thirty thousand bottles of counterfeit Brunello, Chianti Classico, and other high-end Italian DOCG (Denominazione di Origine Controllata e Garantita, or Controlled Designation of Origin Guaranteed) wines. DOCG is the highest legal classification given wine by the Italian government, “guaranteeing” quality. But these were cheaper wines put into expensively labeled bottles, complete with fake official DOCG seals. By the time police made arrests, bottles had been sold in retail stores and served in bars and restaurants. The following month six hundred bottles of similarly packaged faux high-end Barolos were seized. A year earlier, two fraudsters had netted more than two million euros—over $2,500,000—by selling just four hundred bottles of cheap wine repackaged as one of the world’s most coveted and collectible French Burgundies. That’s over six grand a bottle, made possible in part because the bold duo chose to also label the wines with a faux-standout vintage.

While insidious, this type of purely criminal fraud is largely skipped over in the coming pages, with a few notable exceptions such as olive oil and seafood. There are two reasons for this: First, as Fake Food issues go, it’s a small one. Second, there’s really nothing you can do about it, no matter how closely you read the label. These are crimes, pure and simple, akin to a pickpocketing or having your car stolen off the street, the victims being consumers in the wrong place at the wrong time. Unfortunately, crime exists, and always has, in every society on earth. But all the other types of food fraud described herein, even when also criminal, are more common and more preventable.

UTTER IMPOSTORS

This is the worst level of common fakery, an unapologetic take-no-prisoners approach to swindling consumers, which simply substitutes an unrelated product for the thing it pretends to be. At least the illegal counterfeiters mentioned above had the “decency” to use cheap wine in place of good wine, an act known as an economic fraud, where damage is measured chiefly in dollars. But what if they never even used wine at all? What if they used something potentially lethal instead? In 1986, Italian winemakers substituted toxic methyl alcohol for grape-derived alcohol, killing more than twenty people.

These kinds of product swaps have been going on since ancient times, and in London at the turn of the eighteenth century it was commonplace for merchants to take readily available leaves, chop them up, roast them, darken them with slightly poisonous dyes and pass the mixture off as Chinese black tea. The worst version was “green tea,” dyed with much more poisonous copper. A more contemporary and highly publicized example is the widespread European horsemeat scandal of the past few years, where cheaper horsemeat was found to have been widely substituted for beef, especially in processed foods.

There is no way for the average consumer to look at a bunch of ground-up leaves in a teabag or chopped meat in frozen lasagna with the naked eye and positively identify it. This visual ignorance is a recurring Fake Food theme we will see in our restaurants and supermarkets.

This type of fraud, selling fiction, is just slightly less common today, in an era where accurately testing the contents of food is easier. But it is still happens much more than you would think, and far less testing or inspection of our food supply is “done than most people believe. Most of the foods we eat every day are produced or imported, labeled, and sold with almost no oversight at all. In certain food categories, this kind of utter impostor fraud is so regular as to be a public health risk. For now, let’s just say that if you are drinking a cup of herb tea as you read this, you might want to put it down for another hundred pages or so. Pour yourself a Scotch whisky instead, one of the few reliably Real Foods.

While often just as criminal as illegal counterfeits, utter impostors are systemic in nature and with knowledge you can protect yourself against these fakes. The first step is to learn which foods are most at risk, and the second is to shop for these particular products from more reliable vendors or producers. In this case, our own government is also much more to blame, because perpetrators are so rarely punished. Those wine counterfeiters were arrested, but in most cases where fish, tea, cheese, or any other food is intentionally sold as something else, no matter how dangerous the deception is, the result is a slap on the wrist or warning letter—if that—which amounts to de facto decriminalization. Counterfeit wine represents a tiny fraction of the wine market, but in many cases counterfeit fish is the market.

LEGAL AND GRAY-AREA COUNTERFEITS

This is where we get into a moral area on which some readers may not take my side. Earlier I defined Real Food as being what it says it is. By this same logic, when a manufacturer intentionally misleads the consumer into thinking she is buying something different (and usually better) than the actual product, the result is a fake, even if no law is broken. There are plenty of legal Fake Foods—like the California “Burgundy.”

If you adhere to the philosophy that businesses and individuals should be able to do whatever they want and get away with whatever they can, as long as they do not break laws, even when the laws are clearly inadequate and the behavior is harmful and/or dishonest, then you probably will have trouble accepting these foods as fake. I hope to convince you otherwise.

Let’s use a dramatic hypothetical example: Suppose that instead of the United States you live in Russia. Now suppose the Russian government decides to shore up the domestic auto or computer industry by making it legal for Russian companies to produce specific “American” products using the same brand names. Suddenly, you can buy a copy of Microsoft Office not made by Microsoft, but rather by some local teen, which might lack certain important components, such as Word and Excel. Likewise, you can buy a Cadillac Escalade, but instead of an SUV made in Detroit costing seventy-five thousand dollars, it might be a sedan made in Tolyatti costing seventy-five hundred dollars.

In this hypothetical new world where Russian law allowed all this, would American manufacturers like Cadillac and Microsoft become incensed? You bet. Would the U.S. government formally and vigorously protest? Uh-huh. The Russian manufacturers of these products would not be able to export them, except maybe to North Korea or China, because in most civilized countries they would be considered obvious counterfeits and banned. But the Russian and Chinese market is more than big enough to support its own domestic fakes of these well-known brands.

At the end of the day, who would be affected? First, the Russian consumer who thinks he is getting the quality, features, compatibility, and support Microsoft is known for, but is not. That is an economic fraud. On the other hand, the Russian owner of “Microsoft” is getting rich and is much better off under this arrangement, as long as he can sleep at night. The manufacturers of the real products are adversely affected because they are losing sales to the fakes, often unwittingly. Suppose a rich oligarch who knows of Cadillac’s global cachet and reputation for quality and who can afford a real Escalade buys the fake, thinking he is getting the real thing. Now the damage mounts: The buyer suffers economic fraud and potentially injury or death if he has an accident in this far less safe “Cadillac.” But the real Cadillac also suffers harm, as does the autoworker in Detroit who loses his job because sales are down in the Russian market. Would the respective CEOs of the affected American companies consider these Russian products real or fake? It wouldn’t matter, because in Russia they’d still be legal, just like our “Burgundy” here.

This scenario brings up a key point about the Real Food, Fake Food issue. Most Real Foods are not recipes; they are executions of a process. Earlier I mentioned onions and corn, and how planting the exact same seed, kernel, or bulb in different places will yield vastly different results. You can make a 100 percent pinot noir wine in Oregon that might be as good or better than one from Burgundy, but it will never be the same, even if using identical vines and winemaking techniques, because the soil and weather are different. Burgundy is essentially a brand name for a particular style of wine. Others can make the wine in the same way, but they should not be able to call it by the brand name Burgundy. Parmigiano-Reggiano is a “brand” of cheese, with three different “models,” just as Cadillac is brand of car. Cadillac can legally protect its name but cannot claim an automobile exclusive—there are lots of other brands of cars. But in all these cases, the name or brand also connotes unusually high quality. The confusing issue is that the United States has a different trademark law system from France and Italy, and ours does not allow trademarks to be collectively owned. Cadillac is one company, while Parmigiano-Reggiano is a consortium of companies.

I know the Russia example sounds farfetched, but a real version of this situation is unfolding right now on a smaller scale—with pizza. Dating back seventy-five years, Brooklyn-born Grimaldi’s is one of New York’s most popular and iconic pizzerias, and there is usually a long line out the door at the flagship. It is famous for using coal-fired ovens, not typical for New York – style pizza, giving it a distinctive taste. Grimaldi’s has parlayed its successful original into a brand name known for both a particular style of pizza and excellence making it, and it has grown into a national chain, with nearly fifty restaurants in a dozen states. It’s not quite a McDonald’s or Chipotle in scope, but it is a significant food undertaking, all built on the presumption that its brand and long history of delivering a high level of product quality means something to customers—just as it does for Cadillac. Other companies can make cars, but they can’t make Cadillac cars. Other companies can make pizzas, but they can’t make Grimaldi’s pizzas. Unless they are in China.

The owners of the real Grimaldi’s woke up one morning to find their pizzeria had been carbon-copied in Shanghai, right down to signage and T-shirts identical to those their staff wears, emblazoned with the signature slogan “I’m gonna make you a pizza you can’t refuse.” Because the real Grimaldi’s appears in every New York City travel guidebook, including those published in Chinese, and there are often many Chinese visitors waiting in the Brooklyn line, it obviously has a quality perception in Shanghai worth trying to cash in on—otherwise there would be no need to steal the name; Chinese pizzerias could just attempt to make a similar type of pizza. Many winemakers make wines in the style of Burgundy without using the name, and in fact, the only ones who do use it are selling the lowest-quality imitations. The real Grimaldi’s sued a former employee involved in the “clone” for twenty-five million dollars.

Immoral? No doubt. Illegal? Well, considering the “Parmesan” standard, that depends on whether the real Grimaldi’s folks had appropriately trademarked their name under Chinese law. Or maybe the Chinese government will deem the word Grimaldi’s to be a generic term for high-quality pizza and thus incapable of trademark protection, as the United States has done with Champagne.

Regardless, Grimaldi’s has spent decades building a lofty reputation for its distinctive take on pizza, and that reputation has been hijacked, known in trademark law as riding the coattails. Even if it doesn’t hurt the owners economically (which of course it does), it hurts them because it is wrong, and at the end of the day, that may be enough.

Besides an attempt to mislead consumers, another reason producers usurp existing product names is to make it easier to explain what they are selling. In Switzerland, most people understand what real Gruyère cheese is without further explanation. But when a U.S. manufacturer makes a Gruyère-style cheese and doesn’t want to lie and call it Gruyère, that honest cheese maker is faced with a tough choice of how to convey to the consumer what type of cheese it is—a unique name like “Joe’s Great Cheese” might not do the trick. So at this point I will make an important clarification in the scheme of Real Foods and Fake Foods: I’m a big fan of using the terms imitation and style when advertising inauthentic products because they offer a transparent solution to many of these issues. Since these words clearly alert consumers that what they are buying is not the genuine article, consumers cannot accuse producers of acting in bad faith. Imitation Gruyère is not Gruyère (though it still might be real cheese). Similarly, if you see a sign for Kansas City–style barbecue, it’s a sure indication that you’re not in Kansas (or Missouri) anymore. For this reason, I heartily suggest the use of such modifiers as imitation Kobe or Parmesan-style, because no matter how good they may taste, if the Kobe isn’t from Japan and if the Parmesan isn’t from Parma, they are not what they purport to be.* (Interestingly, one of the largest U.S. tobacco product retailers, JR, sells “Genuine Counterfeit Cuban Cigars,” which it describes as Cuban-style made in Nicaragua. Few if any consumers would confuse that with the real thing, and I can definitely live with counterfeit as a modifier—it is often the most accurate one!)

What I can’t support, however, is the use of domestic and similar terms as qualifiers. While, yes, clarifying a product’s origin (e.g., “domestic Kobe” or “California Champagne”) will signal its inauthenticity, it also places an unfair burden on less-savvy consumers, who must now memorize the history and source of all Real Foods. The simple reality is that there can be no such thing as “California Champagne,” since by definition Champagne cannot be produced there. Therefore it should not be advertised as such.

Now, what about foods labeled “natural,” “pure,” or “100% something or other”? This is another gray area since these terms have little or no legal definition but are often intentionally used to dupe buyers. In general, the law allows these claims to be slapped on almost anything, and manufacturers take advantage by applying them to products in confusing—and sometimes ridiculous—ways. During a court case between hot dog giants Ball Park and Oscar Meyer, in which Kraft defended its “100 percent pure beef” label on Oscar Mayer hot dogs, Stephen O’Neil, the attorney for Kraft, “told the judge that the 100 percent beef tag was never intended to suggest there weren’t other ingredients.” The hot dog makers later settled their lawsuits. In this case, the manufacturer apparently meant that whatever beef was in the hot dogs was in fact beef but did not clarify how much of the hot dog comprised beef. Which informs consumers not at all.

But when using such disingenuous labeling, there is a line that can be crossed, as the law also generally prohibits marketing that “misleads.” In reality, misleading consumers is a far higher standard than you might think to prove, and it is resolved only through lawsuits on a case-by-case basis.

Kobe beef is solidly in this gray area. There is no doubt that almost all of what is sold in this country as Kobe beef is fake, but since there is no law specifically prohibiting it, Faux-be beef would appear to fit the bill of a legal counterfeit. Consumer lawsuits for this kind of food fraud rarely come to fruition unless they are class-action suits involving enormous numbers of transactions and deep-pocketed perpetrators. This excludes most individual restaurants, leaving them free to ride roughshod over customers with all sorts of fictional menu claims.

Masa Noda is an attorney, specializing in trademark law with the New York firm Greenberg Traurig. He has been trying to help protect Kobe beef through the legal strategy of chipping away at trademark infringement. As he told me, “I too have been bothered by the use of ‘Kobe beef’ on restaurant menus over the years. I took it on not for the money, but for the principal, so that people won’t be deceived. When people hear ‘Kobe beef,’ they think, ‘Oh that’s something good,’ so there is definitely consumer deception going on, no doubt. But once you learn that natural means nothing, organic means nothing, you learn that you need to go only with what you trust. But the more you learn, the less you trust.”

*It should be noted that the European Union wholly disagrees with me on the use of imitation, style, and similar designations. Its rules for geographic indications on foods emphatically states, “Registered names shall be protected against any misuse, imitation or evocation, even if the true origin of the products or services is indicated or if the protected name is translated or accompanied by an expression such as ‘style,’ ‘type,’ ‘method,’ ‘as produced in,’ ‘imitation,’ or similar” (EU Commission Regulation No. 1107/96, art. 13). These rules would ban such disclosures as “imitation Kobe beef.”

No Comments