In our final weekly ParentSpeak challenge, author Jennifer Lehr asks you to spend a week trying to identify the places your child “acts out,” and the fundamental needs behind this behavior.

Kids may scream. Play too roughly. Whine. Hit. Drag their feet. Not listen. And otherwise act in ways that frustrate, annoy, and infuriate us.

And we want tools to make it all go away.

Usually, we call these tools “discipline.” We may start with a warning. We may escalate to screaming. Or we may threaten a time out or to take away privileges. We may even resort to hitting (aka spanking) them so they’ll stop ALREADY. And then all will be well.

But it won’t be.

The situation will actually become worse, even if it may seem better for the moment. This is because punishment may scare a child into “behaving himself,” but it won’t help address the underlying feelings and needs driving the behavior. If a need is not met, the child will continue to try to meet it in some other way. Because needs don’t just go away. So punishing a child only creates more problems without truly solving the original one.

Needs? What do I mean by that?

There are only a handful or so of innate human needs. They are the same for all people across all time.

Needs aren’t wants. They’re not I need that toy. Or I need to go to Disneyland. Those are merely ways of satisfying needs, and there are an infinite number of ways to do that—some healthy, some not so much. Rather, needs are more like I’m hungry and need food, I’m lonely and need companionship, and I’m curious and I need to understand.

In 1943, the great humanistic psychologist Abraham Maslow identified five fundamental needs:

- Physiological Needs (food, water, warmth, rest)

- Safety Needs (security, safety)

- Love & Belonging Needs (intimate relationships, friends)

- Esteem Needs (feeling of accomplishment)

- Self-Fulfillment Needs (creative activities, achieving one’s potential)

All human behavior is motivated by a need (or two or three). As Maslow explained, “Any motivated behavior . . . must be understood to be a channel through which many basic needs may be simultaneously expressed or satisfied. Typically, an act has more than one motivation.” For example, a baby nursing is at once satisfying her physiological need for sustenance, as well as, perhaps, her need for safety and love. Similarly, by writing my book ParentSpeak and this article, I am at once satisfying my need for safety (financial resources), esteem (achievement, respect of others), self-actualization (creativity and problem-solving), and self-transcendence (helping others).

And so it stands that if a child isn’t responding to a reasonable request, then their behavior must be meeting a more pressing need.

I think an example will help illustrate what I mean.

Mornings were getting to be frustrating for my friend Patrick. And he was at a loss of what to do.

He explained, “Since Roy [his husband] leaves for work really early, it’s just me and the boys. [Aiden was two and a half and Ethan almost eight months.] And basically we have a routine: We get up, I get the boys dressed, and first I serve Aiden his cereal then I sit next to him to feed Ethan on my lap. Simple! But inevitably, every single morning just when Ethan is opening his mouth for his first bite, Aiden climbs up on the table and starts hitting our chandelier.

“So at first I told him very calmly but firmly, ‘Please come down. Tables aren’t for climbing. Tables are where we eat.’ But he didn’t listen. Which actually isn’t like him. He just stayed up there hitting the damn thing.

‘That’s very delicate. Please don’t hit it anymore,’ I’d say. But he kept on hitting it.

“So, totally frustrated, I’d have to put Ethan in the Pack ’n Play, pick Aiden off the table, and tell him, ‘I’m not going to let you climb up here anymore.’ Then I put him down and pick Ethan up and start over. And then Aiden just did it again! I figured he was trying to test my limits, right? I figured there were only so many times he’d do it before he got the message that I won’t stand for it. I figured he’d get tired of the whole routine. But it just went on and on.

“Eventually, of course, I lost my patience and yelled at him. But even that didn’t make a difference. Finally when the babysitter would walk in, it was such a relief. But then I’d leave Aiden for preschool so mad at him.

“But everything changed when I understood the idea of needs driving behavior.

“I wondered, What need was Aiden trying to meet by hitting the chandelier? And almost as soon as I asked myself the question, I had an answer. Connection. Belonging! I figured that Aiden was feeling left out. He was probably jealous of the attention I was giving his brother that I used to give him. He’d had a couple years of my undivided attention every morning, and now I was focusing much of it on Ethan! It wasn’t brain surgery, but I’d never thought about it before.

“So the next morning instead of sounding like a broken record saying, ‘We don’t climb on tables,’ I said, ‘Aiden, every time I’m about to feed Ethan, you climb up on the table and hit the chandelier, even though you know I don’t want you to. It tells me you have some very strong feelings about me feeding your brother. Are you feeling left out?’ He looked down.

“Well, if you are, I can understand that. Before Ethan came along you had all of my attention at breakfast time. I don’t want you to feel left out. I love being with you. Hmmm, I wonder what we can do to include you when it’s time to feed your brother.

“I could see him thinking, but he didn’t say anything. So I threw out an idea: ‘Would you like to help feed Ethan?’ I asked.

“Aiden lit up. He climbed right off the table himself, without me saying a word! He sat right next to me and fed his brother with me. And he was proud! He felt so much a part of the family. And he’s helped feed Ethan every day since. He just wanted to feel included. Problem solved!”

If your child isn’t responding to a reasonable request, it’s likely that the behavior is trying to meet a more pressing need.

This week, perhaps wonder what need that might be? Can you identify it?

What might be a more healthy way to meet that need?

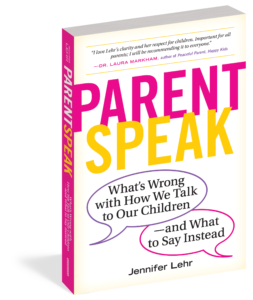

About the Book:

About the Book:

A provocative guide to the hidden dangers of “parentspeak”—those seemingly innocent phrases parents use when speaking to their young children.

Imagine if every time you praise your child with “Good job!” you’re actually doing harm? Or that urging a child to say “Can you say thank you?” is exactly the wrong way to go about teaching manners? Jennifer Lehr is a smart, funny, and fearless writer who “takes everything you thought you knew about parenting and turns it on its ear” (Jennifer Jason Leigh).

Backing up her lively writing and arguments with research from psychologists, educators, and organizations like Alfie Kohn, Thomas Gordon, and R.I.E. (Resources for Infant Educarers), Ms. Lehr offers a conscious approach to parenting based on respect and love for the child as an individual.

Buy the Book

Amazon | B&N | Indiebound | Workman

No Comments