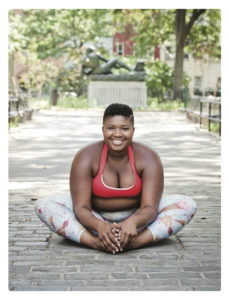

At this moment when Americans are embroiled in so many debates regarding inclusion and exclusion, the story of Jessamyn Stanley, a pioneering queer black Southern woman who advocates for having room on the yoga mat for bodies of all sizes, colors, gender expressions, and sexual orientations resonates beyond the realm of yoga to the politics of our time.

Stanley’s debut book Every Body Yoga: Let Go of Fear, Get on the Mat, Love Your Body presents a paradigm shift in the approach to yoga for every person whose aspirations have been tempered by body shame or insecurity.

Buy the Book

Indiebound | B&N | Amazon | Workman

Scroll down for an excerpt from the book.

The Elephant in the Room

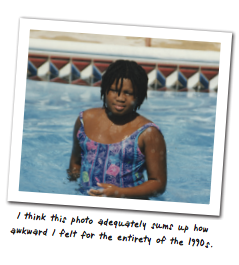

Here’s the thing: I’m fat. And I’ve always been fat. Well, maybe not always. I suppose most doctors would say I had every opportunity to be a normal, happy, thin kid. But instead I turned into a fat, occasionally smelly, supremely awkward weirdo. My mom has always blamed my early weight gain on the lunches served at my elementary and middle schools. She abhorred the chicken fingers, lasagna, and sloppy joes that my public schools dished out, chock-full of the toxic shit that’s been making Americans fat for the past hundred years or so. But frankly, the food we ate at school wasn’t all that different from the food I was eating at home.

Here’s the thing: I’m fat. And I’ve always been fat. Well, maybe not always. I suppose most doctors would say I had every opportunity to be a normal, happy, thin kid. But instead I turned into a fat, occasionally smelly, supremely awkward weirdo. My mom has always blamed my early weight gain on the lunches served at my elementary and middle schools. She abhorred the chicken fingers, lasagna, and sloppy joes that my public schools dished out, chock-full of the toxic shit that’s been making Americans fat for the past hundred years or so. But frankly, the food we ate at school wasn’t all that different from the food I was eating at home.

I grew up in a traditional black Southern family. Holidays meant deep-fried turkeys, vats of pork-coated collard greens, lard-rich meat gravy, and plenty of fresh biscuits to soak up all the juices. My mother resented this gastronomical heritage with the fiery passion of a thousand suns. She saw what the traditional foods of our homeland had done to our family members, making diabetes and heart disease common among older and younger generations alike, and she wanted a different future for her family.

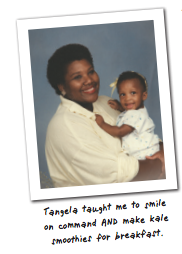

Tangela was part of the late-1980s wave of feminist mommies. These were college educated, post–second wave women who exhibited their love of their children by absorbing every bit of doctor-approved, nutrition-related gobbledygook available. My mommy denounced the ham-hock-drenched veggies and fatback-laden diets of her heritage. Our family was solidly working class, but she tried her best to mesh our meager food budget with the health ideals she read about in books and magazines. She was a devotee of Susan Powter, and was willing to try every new holistic dietary trend under the sun. Way before Jessica Seinfeld was sneaking spinach into brownies, Tangela had her eyes peeled for opportunities to trick us into eating the food she read about in her favorite hippiedippy magazines and books. She had us drinking kale smoothies and eating chia seeds before they were on the radar of every healthy-living food blogger under the sun. She was all about echinacea and other green supplements, and her Jack LaLanne “Power Juicer” was one of her most prized possessions.

Tangela was part of the late-1980s wave of feminist mommies. These were college educated, post–second wave women who exhibited their love of their children by absorbing every bit of doctor-approved, nutrition-related gobbledygook available. My mommy denounced the ham-hock-drenched veggies and fatback-laden diets of her heritage. Our family was solidly working class, but she tried her best to mesh our meager food budget with the health ideals she read about in books and magazines. She was a devotee of Susan Powter, and was willing to try every new holistic dietary trend under the sun. Way before Jessica Seinfeld was sneaking spinach into brownies, Tangela had her eyes peeled for opportunities to trick us into eating the food she read about in her favorite hippiedippy magazines and books. She had us drinking kale smoothies and eating chia seeds before they were on the radar of every healthy-living food blogger under the sun. She was all about echinacea and other green supplements, and her Jack LaLanne “Power Juicer” was one of her most prized possessions.

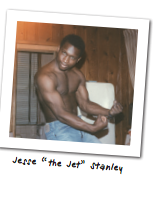

Much to her chagrin, Tangela’s baby daddy (also known as my loving father) was and continues to be a stone-cold macaroni and cheese and root beer aficionado. Jesse Stanley has always been a physical powerhouse—he was a celebrated athlete and bodybuilder in his youth, allowing him the metabolic freedom to eat whatever he pleased. Along with a tendency toward social introversion, my father passed his love of cheddar, noodles, and mountain soda brews to his children. And anyone who thinks that even the BEST kale smoothie can compare to even a single sip of crisp, ice-cold Barq’s root beer is just kidding themselves. So despite our mother’s best efforts, my brother Gabriel and I happily ate our way toward chubby bellies, plump thighs, and juicy neck rolls.

And if I’m really being honest, my fatness wasn’t just the product of extra helpings of mac and cheese on Thanksgiving or the quintessential Stanley family special-occasion Golden Corral buffet pig-outs. No, just like a lot of true food addicts, my complicated relationship to food was born out of a place of sadness, not celebration.

And if I’m really being honest, my fatness wasn’t just the product of extra helpings of mac and cheese on Thanksgiving or the quintessential Stanley family special-occasion Golden Corral buffet pig-outs. No, just like a lot of true food addicts, my complicated relationship to food was born out of a place of sadness, not celebration.

Back in 1995, shortly after she returned home from an epic voyage to the Fourth World Conference on Women in Beijing, my mom became very sick. I mean, really sick. I was eight years old. At first, it didn’t seem like that big of a deal. Kind of like a really bad cold, you know? But the cold just kept getting progressively worse. And eventually my mom’s body started retaining excess water. Like, a lot of excess water. She started to swell up like Violet Beauregarde in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Eventually, she was almost completely bedridden—her body was congested with all kinds of fluids, and she was constantly coughing up chunky streams of brown, yellow, and green. My parents sought out all kinds of medical specialists, but she was continuously misdiagnosed. Our lives starting moving to the morose rhythm that only sickness and sadness can orchestrate.

Due to my mother’s mounting medical bills and his status as our family’s sole breadwinner, my beloved papa bear was forced to work round the clock to keep our little nuclear family afloat. Responsibility in hand, Jesse spent the first two decades of my life pulling night and day shifts at two different jobs. In fact, most of my strongest childhood memories of my dad are of stolen moments early in the morning and late at night when he would have an odd hour between shifts. He always made time to answer homework questions or listen to my complaints or fears about enemies and various obstacles, but, understandably, the few hours of his day not logged on an employee time clock needed to be spent in a state of sleep and energy restoration. And because my mom was basically bedridden for the majority of late 1995 through early 1998, my brother and I would comfort each other by watching VHS tapes of musicals and eating everything under the sun.

I’m sure my mom would love to think we were making ourselves brown rice pilaf and kale chips while she was out of commission, but that was so not the case. We were kids, for crying out loud—my brother wasn’t even old enough to reach the stove. We ate a lot of ramen noodles, which are infamous for their high sodium content and complete absence of nutritional value. This went on for longer than anyone could have expected, and my brother and I both quietly ballooned in size. Along with physical girth, we both gained a host of new body image problems that would be a nuisance for years to come. Three major surgeries and nearly two decades later, my mom’s health has greatly improved—but it took nearly that same amount of time for me and my brother to address the body image problems we accumulated during those dark days.

What a Cliché

As I pick through the emotional rubble from that very blue period in my family’s life, I can find all the building blocks that eventually became the bedrock of my yoga practice.

As I pick through the emotional rubble from that very blue period in my family’s life, I can find all the building blocks that eventually became the bedrock of my yoga practice.

I’m fully aware that my experience is the opposite of unique. For every maladjusted human being walking around on this planet, regardless of gender expression, there’s a story just like mine. The details may vary, but the themes are basically the same: a cornucopia of self-imposed and society-endorsed body issues, with a barrage of unhealthy coping mechanisms sprinkled liberally on top.

I actually take a lot of comfort in the fact that this kind of sadness is such a common shared experience—ultimately, it’s kind of the great unifier, isn’t it? That’s why I find it so strange that our shared alienation tends to be the first thing yoga teachers try to bury or hide while leading a class—they glorify life’s sunshine and rainbows, but then completely fail to mention its dark, bittersweet moments. This baffles me because I think my yoga practice would be indescribably monotonous without the chaos of my daily life.

Because, make no mistake—I’m not naive. I don’t think the shitty parts of life are over for me just because I’ve cultivated a vigorous yoga practice. On the contrary, I think shitty things will continue to happen. But that’s life. The fuckery never ends. Any attempts to control or anticipate the crests and valleys will only yield dissatisfaction and disappointment. Instead of trying to micromanage my emotional journey, I use yoga to pull up off the gas and help me see my life objectively and without judgement. It may not be foolproof, but it’s the best tool I’ve found so far.

So maybe now you’re thinking, “If yoga is so great, why isn’t everyone all over it? Why is there such a narrow vision of yoga practitioners? Obviously it’s not just wealthy white women who can benefit from the eight-limbed path, right?” I feel you, dude. I have thought these exact same thoughts. So enough about me and my “body issues”—for now, anyway. Let’s get a better idea of what yoga actually is and how you can fit it into your own life.

Extras

Jessamyn Stanley introduces herself.

Peek inside the book.

Check out Jessamyn’s Instagram.

No Comments